On or about the 9th January 1977 the building was awash with visiting people from Bangladesh. Elderly men with intelligent expressions yet jabbering away in their own language. A younger man carrying a bulging brief case could have been a nephew but emerged as the senior of the group. Ibrahim came into my office on the first floor carrying a base on which a model of a “glass house” was fixed.

“Misterstrill” he said, “what you think of this?” offering me the model of the glasshouse. “Maybe we build 2,000 of them, eh? My Father says please come and see him in his office and meet the contractors from India!” (He meant Bangladesh.) “You come please?

I followed him down to Ishaq’s palacious office. Ibrahim introduced me as “Misterstrill” he could never get the aspirate H separate in my name. I didn’t mind. It amused me. I forgot their names immediately as I realised the younger man was the senior in the group. I gave my concentration to him. The older men had, it seemed, come for the ride, it was an air flight from Dacca and I drank in the reason for this meeting.

By some weird method Ibrahim and his Father had been in touch with this engineering group who had ideas of joining with Ishaq’s family business building 2,000 houses over a space of three years for the State of Qatar.

The model house I had been shown was their idea of a sample house they had brought all the way from Dacca and which they proposed to put forward as the type of house they would build. I was horrified not only was it ludicrous to think on these lines it would never be considered in a million years. The 2,000 houses were to be built on an estate to be known as Khalifa Town.

This I knew from gossip and from the local newssheet. I also knew that the Amir Khalifa had said that the recent houses built to the north east of Doha beyond the Radio Station were ideal for Qataris and would be the model for the new houses. Yet here was Ishaq drooling over a ridiculous model of a house built mostly of glass impossible to construct; economically impossible to erect with the type of labour we could recruit in the Gulf even if we recruited from Lebanon at high wages, the time factor for erection was far too long. And when built such a house would be too hot for habitation. A real NO! NO!

The situation was surreal. How could I sort this out? I had nothing to do with the building department that was the sole area of responsibility of Ibrahim the son and General Manager. I did not even know the extent of the arrangement Ibrahim had made with the E. A. H. Consultants from Bangladesh. It came as a complete surprise when Ibrahim opened my office door and showed me the incredulous model of a desert house made of glass panels.

I had to find out what had been going on without appearing to be out of the picture. These were the times when working for a very Arab company one had to hold oneself in and act the part of the specialist even though I was totally unaware of what had gone before. I posed several searching questions to the young man I addressed as the leader of the group. He spoke good English and was quick witted. My questions polite though interrogating gave me a rough idea of their background, for they gave sparse detail yet enough to make me aware they had small assets and smaller backing. At that point in time it was almost thirty-two years since I had worked in Bengal on construction business.

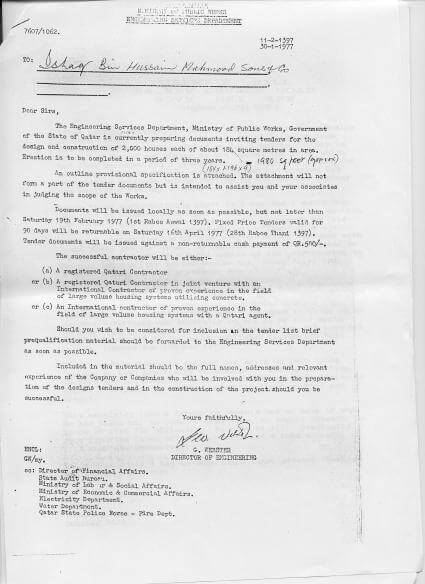

Having made myself aware of what was going on I tackled lbrahim at the first opportunity of what he expected me to do. I wanted nothing to do with this new idea of his. Having been taken around Ibrahim’s building sites, the latest of which was forty, four bed-roomed houses for one of the Sheikhs. I may have unintentionally shown my knowledge of construction when discussing various obvious errors of judgement or style and finish or the sometime lack of on site simple management by allowing gaps in deliveries of material by not having a bar chart. The next day Ishaq asked me to go and see the Director of Engineering of the State Eng, Office and register our company intention of tendering for the building of the 2,000 houses. I was not happy to do this but knowing lbrahim’s lack of knowledge in this field I said I would go and bring back the papers and documents and pay the initial fee. I obtained the papers before lunch. I read them in the afternoon. By six o’clock I had made notes on each salient point. I drove out to the Gulf Hotel and had a small supper. Over supper I relaxed and visualised the number of engineers and employees required for an organisation to deal with the construction of these houses. To design such a chart was a nightmare, I had not done one for so large a scheme.

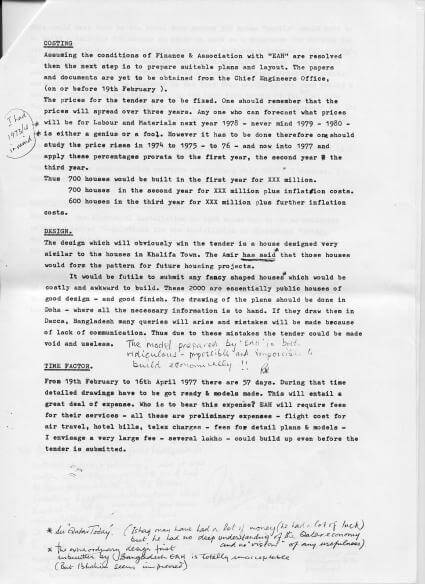

So I went back to the little house and drew out my plan for such an organisation. Then I typed up my response to how best explain to lshaq how he MUST think hard and think deep what had to be done before his firm could think of building so many houses on a state contract. This had to be in simple terms for what I wrote had to be interpreted into Arabic by the Egyptian accountant who’s English and gulf Arabic were wobbly. He must have done it the next day for Ishaq and Ibrahim to understand before they made any commitment with the Bangladesh Group, That is why it is so scrappy and unpolished. I had to warn them what was in front of them before they made another mistake as Ibrahim had done by himself over the recent fiasco!!!Goodness knows why I put in all that effort to get them out of the shit. Professional pride I suppose.

Ishaq bin Hussain Mahmoud and Sons had no chance of winning a contract to build 2,000 houses because they had no chance of ever writing a tender to submit to the Director of Public Works of the State of Qatar. Never in a million years would Ishaq and his sons ever appreciate the magnitude of detail needed on such a project. It was beyond their ken. And the Engineering Group E. A. H. who had flown over from Dacca had no idea and no chance of ever forming an alliance with Ishaq and his company. The very idea was pure fantasy. Ishaq had “plenty money” as they were fond of saying to run a local business before the onslaught of the mountain of debt that was soon to hit them in the year ahead due to Ibrahim’s mismanagement. They had no experience and no reputation for good construction. The Bangladesh Group had no idea of what it was all about and they had no money even to get back to Dacca! What dream had Ibrahim?

I asked the Egyptian accountant to translate my report the following morning much to his dismay. What translation he did and what he presented to the head of the firm I never found out. I only know that glum faces and glummer silence were around for days to come. Ibrahim was not seen around my part of the building for a long time. Ishaq said nothing. When I did see him he passed the time of day and was pleasant, indeed it was one of the only times I saw him smile. It was so rueful I was sorry for him in my heart but it was another debacle avoided.

The forgoing was not an attempt at a tender. It was a paper exercise for Ishaq to learn what he had to face if he wished to tender for the construction of a housing estate of 2,000 houses.