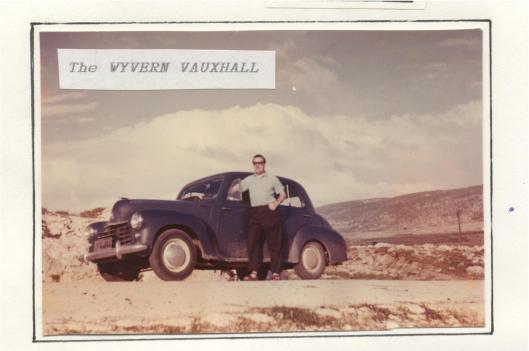

In the summer of 1961 I left Iraq to take up the post of Assistant D.A. in Lebanon. I well remember, I asked the pilot to let the cabin staff know when we were over the Iraqi border and for a bottle of champagne to be brought to celebrate flying out of the repressive atmosphere of the Kassem regime. Other expatriates joined in with more bottles and we were very merry when we landed on the tarmac at Beirut airport. To be in Tripoli and driving in Lebanon was to feel free. I was happy with my work but with so much freedom of movement I desperately needed a car. My luck was in. The personnel manager wanted to sell his Vauxhall Wyvern saloon. It was much older than the almost new Vauxhall we had taken out to Iraq; it was similar to the one I had used in Cyprus. In fact it was eleven years old. But what a car. It gleamed as new; it ran as new, it was a gem. It originally belonged to the workshop superintendent. When work on the pipeline was completed the politicians in Lebanon and Syria refused to allow the Contractor” s labour force to be paid off. The impasse was unresolved for years, which meant a large unwanted labour force milling around under everyone’s feet. The workshop superintendent found a use for four of his quota. He set them to work cleaning and maintaining his car.

When I took ownership the car had the original paintwork on a brilliantly polished body with an engine glistening from the constant attention of daily dusting and cleaning. Underneath the back seat packed in specially contrived trays were spare parts of all kinds, rubber hose and fittings, gaskets, rubber bushes, everything required to keep the car on the road for another decade. I was lucky to be offered such a vehicle and at so reasonable a price.

During the working week we finished around two o’clock so it was easy to motor to Beirut, enjoy a show or a meal or whatever, then drive back to Tripoli by midnight, ready to be at the office by seven next morning.We had many adventures together the Wyvern and I. On the long weekends I would drive to Beirut and enjoy the pleasures of the town staying over either in a small hotel situated between the Phoenicia and the Hotel St. George or later that year in a splendid flat overlooking Pigeon Rock.

There were times when the return from Beirut was delayed which resulted in arriving at the office gates just minutes before the office staff. The car knew the Beirut -Tripoli road better than I did, particularly late at night or in the wee hours of the morning.

Driving the Wyvern in Beirut caused different reactions from drivers in different age groups. The older taxi drivers and more sedate Lebanese took kindly interest in a well groomed, ancient and smiled benignly. Not so the younger element. In 1962 Lebanon was riding high on the crest of the economic Nave. Oil money flowed freely and copiously into Beirut from Arabia and the Gulf States. The younger generation owned the latest in heeled transport, large American contraptions overpowered to cope with the air-conditioning system and bedecked with yards of unnecessary chromium trip or they drove suave Mercedes and B. M. Ws. My old Wyvern was, to them, a jalopy.I learnt to drive like a Lebanese and had fun with many of the younger drivers one encountered on the main Beirut road. They scorned such an ancient vehicle. When they drove by in their modern cars, provided they were not large American or German Mercedes I would let them hoot past and then sit on their tail almost all the way to the city and then wham! In the last mile shoot past them! Indeed one evening I raced a rear engined American car almost all the way from Jounie to Tripoli until it’s engine packed up in a cloud of black smoke.

Driving in the city was precarious. Particularly if surrounded by horn blowing excitable young fellows in flashy cars. Road discipline was almost on existent. It was the rule of the fastest and the brashest. Faint heart meant a bent fender and a curse for good measure. One had to play the game according to their rules and no matter how one was intimidated the only course of action was to drive straight on and the weaker fell away and let one through. Many is the time I almost gave way fearing to wreck the paintwork or worse still bend the body or lose a fender. Truth to tell the Lebanese were smart and gifted drivers who swerved or braked on the split second to avoid mishaps. This made me all the more determined it was not going to be me doing all the swerving and braking. I like to believe my driving skills were honed by the practice I exercised in taking on the taxi drivers of Beirut. The Wyvern and I earned respect, in both style and performance.

The only time she came under fire was on a simple jaunt just outside Tripoli. One balmy afternoon driving north along the main road toward the refinery I turned off on to a small track which went round the back of the village of Beddaoui. The track wended its way up the very high hill over- looking Tripoli. Jebal Terbol. Rounding a corner I realised too late that the track also went through the Palestinian refugee camp. The relations between the Lebanese and the Palestinian refugees were at that time fairly easy and stable. My progress through the camp merely caused a few catcalls from little children. I concentrated on driving the Wyvern up the bumpy track to the top of Terbol. I knew I had reached the top for the track suddenly finished at the edge of a sharp fall down the other side.

The view was magnificent. A backdrop of snow-tipped mountains and hidden valleys in an arc to the east and the south, whilst to the north and the west the brilliant blue of the Mediterranean. Manoeuvring the car round on the loose gravel and shale at the top was a lengthy task. But we, the car and I, came down easily but had to face a barrage of older children and a few boisterous men waiting and chasing after the car through the refugee camp. Small rocks, rotten garbage, sticks and whatever came to hand rained down on the car that I had the sense to accelerate out of danger. I was sorry for the car and annoyed with myself for taking it up to the top of the Jebal. At first I was annoyed with the Palestinians, yet on reflection I felt a little sorry for them because I had unintentionally invaded their territory, for nowadays, nobody particularly an Inglisi went up Jebal Terbol. They reacted in the only way they knew – chase off the stranger. After a wash down and smoothing off the odd bruise that soon polished away, the old car looked herself once more.

In the eleven months I owned the car we travelled the length and breadth of the Lebanon – or as far south as the Army would allow. I visited Saida several times and managed to get down as far south as Tyr although as soon as I ventured further south the Army turned me back. The journey into the mountains to Marjayoun, Hasbaya and Rachaya, continuing through to Masnaa, and on to Chtaura to visit my friends the Kortbawi family made a wonderful trip. I can still sense the magic of the scenic, twisting roads, winding through tiny villages – dusty rustic dwellings perched wherever a rock would lend support, rushing rivulets of clear cold mountain water, old men lazily passing their days, the shop-keeper in a tiny hamlet with almost nothing to sell. I bought a tin of ancient sardines and some local bread. He had plenty of fizzy lemonade that I didn’t fancy. A clean drink of crystal clear water from a tiny spring in a rock fifty yards away was a better bet.

Chtaura was a mixed village of Christians and Moslems. The church and the mosque were near to each other. At that time and for years past they lived and worked together quite amicably. The Kortbawis were one of the leading Christian families in the village. The father, long passed away, had named his children, male and female, alternately with Christian and Moslem names.

I met Fahim Kortbawi early in my year in Lebanon. Then a junior officer in the tiny Lebanese Air Force he invited me and my two young children, who were out on a summer visit and one of the lady secretaries to his family home in Chtaura. Two of his brothers ran the family wine making business.

They marketed under the label “Bacchus” and managed in a small way to sell some quite good wine.

We were all on a trip out to Baalbek one blistering hot day when disaster struck. Almost halfway between Rayak and Baalbek, some twelve kilometres from either town the rubber hose from the radiator to the engine split wide open. I was perplexed and at a loss what to do for several minutes. Then the foresight of the original owner of the car came into it’s own. Out with the back seat and there, ready and waiting was a replacement hose and a new jubilee clip ready to be fitted. We poured all the drinking water we had into the radiator and drove slowly into Baalbek, filled it up and were ready and roadworthy once more.

I was getting near to the day when my assignment in Lebanon was soon to end and the resident Civil Engineer asked to buy the car. I had several more offers but his was the first and, as he offered the same price I had paid for it almost a year previously, the car was his. Indeed he gave me a cheque three weeks before I left with the understanding the car was mine until the day I went to the airport.

Of all the cars I had owned to that point in time the Vauxhall Wyvern gave me most pleasure. We certainly had many adventures together, some pleasant, some quite hairy and some, having no place in these reminiscences. The car was much older than the Vauxhall I had driven across Europe and the desert to Iraq, yet it was more sturdy in construction, the gauge of metal used on the body seemed heavier and all told it had more appeal as a motorcar.

Vauxhall Wyvern of Tripoli, Lebanon I salute you!