Note:

I’ve added the account of Laurence Wakefield, who was in the Royal Engineers like my father, and on board the Lancastria too, after his son in law David Joy read this account and sent me his father in law’s war memoirs. I’ve also added the Wikipedia entry for RMS Lancastria.

Robert E. Hill

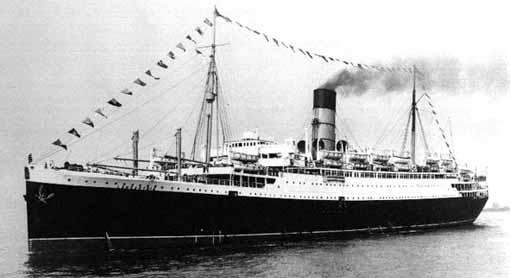

We seemed to take a long time to reach Angers. Some officers and other ranks went off to reconnoitre sites for landing strips but I can’t recall much was accomplished. We eventually reached Nantes where we backed up against thousands of others, Air Force personnel as well as Army. After two or three nights bivouacking outside the town we destroyed the G.1098 stores sabotaged any unnecessary machinery and marched in convoy to the port of St. Nazaire. We arrived on the 17th June at ten o’clock, having marched seven miles many of us in new boots taken from the G.1098 before it went up in smoke. We were tired, grumbling yet knowing nothing of the heroics that had been happening at Dunkirk a month before. At eleven o’clock we went aboard the Cunard’s Lancastria, grousing and grumbling at being among the last to board. We were assigned places on “A” deck aft.

About two o’clock, very hungry we went below and had a jolly good lunch of bangers and mash and hot tea, all the better enjoying silver service by uniformed waiters. Up on top again out in the warm sun, I took off my boots, which were torturing my feet and popped on my ‘plimsolls’. I rested on my kit bag we had been allowed to bring with us.

Teddy Perfect said, “Why the hell don’t we get cracking and weigh anchor we’re a sitting duck waiting here”. Several agreed but each seemed lost in his own thoughts to develop more conversation. Time dragged on. It had been obvious the last few days that we were escaping out of France. We had no news of any kind – just rumours. One of the French troops guarding St. Nazaire had spat at the feet of one of our officers when he wished them goodbye and good luck. With hind sight not a sensible thing to do.

At four o’clock in the afternoon several Stukas flew over. One dropped his bombs and missed by fifty yards, we cheered, and the gunners began to bang away with their ineffective popguns. Another Stuka flew in from the sun on portside. It zoomed low over the ship. We ducked down automatically, a confused chatter of guns a great bang and a smell of cordite. We straightened up and began to yell, “GOT the BASTARD!!” But he had got us. Amidships. Straight down the main staircase. No chance at all for those down there.

Within several minutes the Lancastria began to tilt to starboard. We were wearing life belts, or had lifebelts. I wore mine. Shouts of “OVER THE SIDE”!!! “EVERY MAN FOR HIMSELF”!!! Large rafts were heaved over the side, I helped and waited until most had gone over, anyone in the water with one of them thrown on top would have no chance. A rope ladder was now over the side I got on that and went down as fast as I could boots and feet banging on my head, and one time trapping my hand. By this time the ship was at a terribly steep angle. It is said one sees ones life flash in front of one like a movie. Not so. I was too busy working out what to do and where to go.

By now the sea was full of swimming, paddling, struggling men. I pushed out for a life raft some yards away that was moving away from me faster than I could paddle. I was not a good swimmer. I had the support of the buoyant life jacket yet I did not seem to be able to reach the raft. The ship was towering above me. Spotting a raft surrounded with bobbing heads that seemed to be nearer I struck out for that and eventually grabbed a loop of rope. I was dragged along, next I was paddling with my right hand, then almost pushed down under the raft as it turned in the water. This went on for a very long time.

Temporarily safe I began to think of my family and friends. By now we were sufficiently away from the ship to take stock. The Lancastria had turned over completely with her bottom above the water. Men were scrambling about on her upturned hull. It was uncanny. Would she go down completely or was enough air trapped inside to keep her like that to save the men before they were sucked down. Oil was everywhere. To get far away from the ship to land was everyone’s goal. I was getting tired. A tiny rowing boat painted yellow slid alongside the raft taking people off. I would not let go until I was sure I was ready to get into the boat. In the end I was helped into it by someone grabbing the seat of my trousers as I grabbed the side and missed through sheer exhaustion.

The rowboat put us on to a French trawler; I stripped off my jacket to get dry. A frigate, HMS Havelock, hailed the trawler. As we scrambled up nets to get aboard I lost my jacket. A sailor had taken it from me indicating he would throw it up after me. He did, I missed catching it as the swell was so great the stern end of the trawler dipped down too much as he swung it up to the level of the Havelock deck. It missed by three feet and sank between the screws of both ships.

Gone forever were my papers except for a photograph that was in my shirt pocket tucked behind a metal mirror.

Someone propelled me to the petty officers wardroom. We were fed hot tea and biscuits. We were well out at sea sailing for England when the ship’s ‘tannoy’ broadcast a message that the French Army had given up and Petain had signed the Vichy Agreement. We had little to say. It seemed we had run away. The relief of being alive over rode the gloom and sense of shame. It was all very daunting.

We drew into Devenport. As we tied alongside some well wishers on the dock had little sense. They threw tins of ‘bully’ and other food up to the deck with such vigour we were under a bombardment for a few minutes. One poor fellow having escaped unharmed had his head cut open with a tin of bully. Whilst on the Havelock I had taken off my sodden trousers, someone had taken them away to dry and I couldn’t get them back. I was given a ship’s blanket that I wrapped round me to go ashore. Going down the gangplank I trod on the trailing blanket, tripped and was grabbed by two Wren nurses at the bottom of the gangway. They were going to whip me away in an old world war one, canvas tilted, ambulance. The more I resisted the more convinced they seemed I was a ‘shock” case. I got away and followed the rest to the barrack block close at hand.

Whilst resting for a couple of days we received an issue of fresh uniform and basic gear. After we had been sorted out and our unit or regiment informed, I and a few others of the unit who fetched up at Davenport were detailed to report to Leeds. I telephoned my parents who were delighted. No leave was forthcoming. We were told that would be sorted once we reported to our unit. Leeds Town Hall a magnificent building. We bedded everywhere. I found a space on the stage near the organ console. Joy and sadness abound -ed as members of C. R. E. No.2 found each other. We learned nine personnel had been lost. One was dear old Captain Dennison. The staff sergeant had gone.

Another chap we all missed was ‘Mate’ a driver in H.Q. He had been friendly with all officers, NCOs, and the O. Rs. He was an incorrigible wag. At Nantes he had found some pornographic drawings, exquisitely drafted and beautifully coloured. They were works of art, e’en if very naughty. They were shown to all who wished to see and he had tucked them in his jacket swearing he would give them up to no one. Poor old ‘Matey’ with his pictures at the bottom of the sea. Teddy Perfect who I had last seen going down a rope over the side was his cheerful jolly self other than having both hands bandaged. He had burnt the skin off sliding down the rope.

We shared a posh billet. Our new headquarters were in a large house in Allerton Park. We were billeted in houses nearby. The excitement of going on ‘survivor’ leave was too much. Everyone wanted to know details of the road back from France. My story of the escape after Dunkirk of which people knew little seemed dramatic. The story of the Lancastria seemed a bit over the top. I stopped talking about it other than saying we came out down the Loire valley. “Oh, weren’t you at Dunkirk?” they asked, and lost interest when I said I came out of France at St. Nazaire. The disaster, the biggest loss of life at sea ever, almost 3,000 were lost. Churchill who thought it would be bad for morale suppressed news of the event. It was published seven years later.

Laurence E. Wakefield

1939

March

Joined Territorial Army in Liverpool. Royal Engineers – army trade ‘Surveyor’. Training 3 evenings a week and some weekends. Living and working at Formby. Journey to TA in Liverpool (South) included train full length of overhead railway with view of the ships using the Port.

August

Went to Annual camp (2 weeks) at Halton near Lancaster on River Lune. Bridging camp – pontoons – folding boats – small box girder bridges. At end of 2 weeks kept at Halton – war was imminent. Embodied into Regular Army “Took the King’s Shilling”.

September

War declared. Returned to Liverpool from Halton. Transferred to similar unit at St Helens.

October

Sent to France with British Expeditionary Force. Various locations in France then settled on outskirts of Lille. Worked as a draughtsman on Detailing or Scheduling Steel Reinforcement for construction of strong points on the extension of the Maginot Line. 1940 Applied for a commission. Returned to England – went to York for interview re commission – was accepted BUT on account of my age (22) was told it would be Infantry commission NOT Royal Engineers. This I did not want so returned to France and rejoined my unit. Offered chance to transfer to another part of Royal Engineers “Establishment for Engineer

Services” which I accepted. Went on a course for a month in Brittany – very pleasant during spring – passed out as Engineer Draughtsman (L/Cpl) with indication that I could progress to Military Foreman of Works (S/Sgt). Posted to C.R.E (South) Advanced Air Striking Force at Rheims. Went by train to Paris and on from Gare de L’Est by ordinary passenger train to Rheims.

That was when it all started – there had not really been an active war before that. The train and others on the track were bombed and strafed. When raids finished the British Army other ranks from the train – 12 of us – all individual like myself travelling alone (no units) got together and, as the railway obviously could not function, decided to set out walking. We walked in a southerly direction for a long way and when it was dark we came to a farm which had been abandoned with doors left open – remains of the fire still burning in the grate – cows not milked – the occupants had obviously fled on this first day of the “real war”.

We made a meal and went to bed for the night taking it in turns to keep watch and by morning 6 of the group had gone on. We – the remaining 6 continued walking – 2 went off in another direction, and, after a while, we remaining 4 came up to a railway line and trains were running on that line. We followed it and came to a village where there was a large crowd all waiting to evacuate the area.

Trains came to the station and reversed back to wards Paris. When the French police saw the 4 of us in uniform they were very agitated (they drew their revolvers and we were forced into an air raid shelter alongside the station. A German plane was circling around overhead watching the proceedings. The crowd got much less as the people got away on the train until there were not many left and we thought the train then at the platform would be the last one, so we had to do something to get on that train. There was a van on the train with a sliding door not fully closed, so, as the train started up

slowly, we dashed out of the shelter – shouting – banging our tin hats and generally causing a commotion which took the police by surprise. We pulled the sliding door open and, as the train got going, we jumped into the van. The train got up a good speed and the German planes attacked it, but this time we were lucky and the bombs missed and the train rocked alarmingly, but stayed on the track and we got back safely to Paris where we were taken in for questioning. We were suspect as no British troops had been where we came from. After a few days in Paris, the unit I was trying to join was located at Troyes which was south of the push the Germans were making. I got to Troyes from Paris with no further trouble. The retreat from Dunkirk was in progress but we were south of it and read about it each morning in the papers.

After a short time in Troyes, we moved suddenly to a small village, Aulnay-La-Riviere, south of Paris near to Pithiviers and there we saw something of the evacuation of Paris in face of the German advance. The population came through the village in their thousands – first in cars, buses, lorries etc, then on cycles, pushing prams, handcarts, wheelbarrows – anything that would take some of their possessions – people on foot in all sorts of conditions.

Again we moved on by road – just a few vehicles – we were a small H.Q. unit. We went right across France generally following the Loire until we got to Nantes where we stayed for a couple of days – we were employed destroying documents etc. from British H.Q. at Nantes and then we moved on to an unfinished airfield between Nantes and St Nazaire. There were thousands of British troops there in the open subject to air raids. During the night, we walked on into St Nazaire and into the large transit sheds on the Docks. Our vehicles along with many others were put into a large square formation and were destroyed by fire.

In the morning 2 British destroyers came into the dock and and took off the troops. We went on one of them and thought we were going home – little did we know that most of us were on our last journey and were, in fact, “Going Home”. When we were well out of St. Nazaire (10 miles, I believe) we came to 2 large liners – the one I went to I recognised from the Liverpool Docks – it was a Cunarder “Lancastria”, the other was the Orient line “Oronsay”. When we boarded the Lancastria, we were sent down to the dining room where we had the best meal for weeks served by Cunard stewards. We were then sent back up to make way for the next sitting. With a few of our unit I went to the Shelter Deck (aft) on the starboard side. The ship was absolutely packed with troops plus a few civilians. During the late afternoon we were attacked by German planes – firstly the Oronsay was hit and damaged but remained afloat, then we were attacked. The bombs scored a direct hit and the ship began to sink. At first it seemed to be going on the starboard side, when everyone moved across she righted for a few minutes and then started to go over on the port side.

No life belts had been issued and I decided the only thing to do was to strip off and go in the water and try my luck by swimming. So I went over the side – part way down a rope ladder and jumped into the sea. I was not a good swimmer, but I had to do my best. There were hundreds of us swimming for our lives and the German planes were dropping bombs amongst us, strafing us, and they set fire to the oil which escaped from the sinking ship. I don’t know for how long I swam, but I was about all in when I suddenly came near to an open boat – a lifeboat from another ship. I managed to get up to it and hung on to the lifeline along the boat and, when I had recovered somewhat, I was pulled into the boat. I remember that my reaction was that I could not stop talking! I took over an oar and so helped to get the boat up to a British armed trawler, the “Cambridgeshire”.

The trawler was packed with survivors – some 600 I believe – on a trawler! The plan was to go back into St. Nazaire but the tide had gone out and the vessel would have grounded, so we were taken to the “John Holt” – a Birkenhead cargo ship. We were put in the hold and forbidden to show our faces. The hatches were put on and our luck was really in – we sailed round the occupied coast of Brittany and got to Plymouth without incident. We were taken to a hall of some sorts wrapped in blankets, which were thrown from the quay on to the ship. That blanket was all I possessed and it wasn’t really mine.

The Lancastria sank in 20 minutes after the bombs hit her. The casualties were enormous – just over 2,000 survived – there is no accurate count of the number that perished as it was not known how many were on board, but it is thought that at least 4,000 lost their lives.

As she went down, singing could be heard across the water from those about to perish, “Rollout the barrel” and “There’ll always be an England”.

Our unit lost several members, but, because we were on the open deck, we were luckier than those who were below. They stood no chance. I owe my life to the fact that I could swim – albeit poorly, and the open boat which suddenly appeared – in answer to my prayers I’ll always believe.

The Lancastria sank on 17th June 1940 – a fortnight after the end of the Dunkirk evacuation. It was probably the worst maritime disaster in British history in terms of lives lost.

We were given basic clothing etc at Plymouth – the first thing the Army gave me was a razor!

We went by train to Leeds, spent the first night on the floor under the Town Hall and next day were taken to compulsory billets in the area – “How many bed spaces have you got, Missus? Right – next 3 in here!”. I went to a Jewish family in Chapeltown who treated me very well.

The unit reformed at Leeds. I was out-stationed at Lincoln and Sybil and I were married at Crewe Green on November 9th 1940 – I went back to Leeds.

Wikipedia

Lancastria links

|

The HMT Lancastria Association remembers and honours all those who were present or who lost their lives in the Lancastria disaster. |

|

The HMT Lancastria Archive has many survivor accounts of the disaster. |