An early start had been agreed for eight thirty but as Robert was still packing and had other domestic problems to attend to it was almost an hour later when the car was sent for. Jayanta and Ariyadasa had assembled the baggage at the bottom of the partly made up drive when the car arrived. The driver, Ratnapala seemed somewhat crestfallen as he surveyed the pieces to be packed. He opened the boot lid; two very large speakers took up all the space. Without a word being spoken he looked sheepishly at Robert and dumped the speakers at the side of the road and started loading the bags.

I would have been more comfortable in the front seat but in consideration of Robert’s feelings I sat in the back of the car with him and Jayanta. It was a tight fit. My weight added to the heavily laden boot and did not give the driver much leeway over the bumpy roads, but it caused him to drive slowly allowing me to see much of the countryside and study the local people. Driving through Unanwitiya village, heads turned to watch our progress, Robert was very happy. I could sense his pride as he leaned slightly forward and showed off his friend, the Mahatihir. We drove on through Baddegama and on the back roads out of Galle joining the main coast road on the south side of the city. The coast road, the A 2 running tightly by the shore from Colombo to Hambantota appeared to have had no major maintenance since it was first constructed. Great chunks had been punched from the edges of both sides and what remained was riddled with potholes large and small.

We drove on through Unanwatuna and Talpe a few miles south of Galle, past several signs advertising the “Sunset Inn” and “Beach Resort Hotel” and other guest houses each seeming to have its own private cove or beach.

“The hotel I booked you into for the first night or two was down that road past the Beach Hotel, right on the seashore” said Robert. “I thought you would like it, it’s cheap – perhaps too cheap and after I had read your letter again I decided you would want to stay in Colombo anyway so I booked you into the Intercontinental”.

“I’m pleased you did”, I replied, “It would have been too long a journey over these roads after such a long air trip and I enjoyed those two nights in the Ceylon Intercontinental but I think the Beach Resort would be worth a visit sometime”.

“Yes, we must have a day or two there, said Robert, they owe me a hundred rupees deposit.”

Ariyadasa sitting up front was fascinated by a lady tourist, as was the driver, Ratnapala for he drove even slower past the couple on bicycles, the man in the briefest of shorts and singlet and the girl in a bikini and the tiniest of bras, both sported long blonde hair.

“Do you see that often? I asked Robert.

“No, what chance have I had? It’s only the second time I’ve been on this road since I came back to Sri Lanka” he replied.

“What do the locals think about it?” said I.

“Nothing much, I should think, for many of them its their bread and butter”, came the rather English reply”, and it’s no worse than Brighton beach, is it?

The mood was spoilt by a Ceylon Transport Board bus hooting past belching black diesel smog. Our driver hooted, I thought in frustration and anger, as we sometimes do in Europe. I was to find out later that it is the custom for the driver of each vehicle to acknowledge a safe pass each time they pass one another in whichever direction.

We were soon approaching Weligama. I asked Robert to point out the island of Tabrobane just offshore. Having read Robin Maugham’s quest for his personal Nirvana it would be interesting to see what made the island so attractive. We stopped at a bend in the road. There it was a clump of palm trees and bushes on a small knoll of rock sitting just a few yards from the coast road. I was disappointed. What little of the house one can see, shaded as it is by the cluster of trees and greenery which cover the tiny islet seemed to be much too near the coast to be sufficiently private. One would have more privacy on a headland. Yet the house seemed, from the outside, to be in a more reasonable state of repair than Maugham described it when he toyed with the idea of acquiring it. Even so, I was not impressed.

Bevis Bawa gives a detailed account of the house and its owners in republished articles he wrote for the Ceylon Daily News years ago. When we called on him at his delightful country house “Brief” in the winter of ’87 he gave me permission to cull freely from the article. Bevis being blind and restricted to a day bed was dependant on his servants for almost all his needs. It was distressing to see him so enfeebled when he had once been so active. In 1934, he had been aide-de-camp to the Governor of Ceylon and went on to serve in similar capacities to successive Governors until 1950. But more of Bevis later, let us see how he was connected with Taprobane.

The story goes that a Frenchman, a Count de Mauny married to a member of the English aristocracy with a Family Tree; the like of which Bevis had never seen before, fell in love with Ceylon and, in time, came upon the little mound of rock in Weligama Bay. In those days it was more pleasantly situated than it is today. Then the beach was wide and uncluttered by the main road that now runs through it. He bought the islet for a tiny sum and proceeded to build his home on it. The house was built as an octagon with rooms off six sides, the seventh side accommodating the entrance hall whilst the eighth side opened on to a veranda facing a vast stretch of sea uninterrupted only by the great ice barrier of the South Pole.

It seems the Count was not a wealthy man. To supplement his finances he set himself up as a landscape gardener. He also used his skill in designing and making furniture, using, I imagine the gifted local carpenters then famous in this area. These two pastimes became lucrative, particularly the furniture. He became ‘fashionable’ and those ‘ in the know ‘ were eager to own at least one piece of De Mauny furniture. The result was a spectacular house set in a flourishing if somewhat restricted garden, furnished with beautiful furniture. The garden decorated with ornate pots and ornaments of his own making and design in Italian style.

When Count de Mauny died the house and island, Taprobane, was bought by Richard Peirera who had been a friend of the Count and admired the place since he was a young lad. He found the maintenance costly and problematic. Taprobane underwent a transformation. The thatched roof was replaced by Mangalore tiles. In an attempt to deepen the well by dynamiting, the water supply disappeared with the resultant bang. The garden ornaments were painted in weather proof pink and with the repainting of the walls of the house the place no longer looked the creation of the late Count de Mauny.

The islet then passed to a third owner, Britto Muttunayagam who doubled as a dentist and a professor. He showed little interest in staying there. He repaired the small pier and fixed a gate with the warning to trespassers to keep well away. As he lived in Colombo a hundred miles to the north he soon tired of the place and so Taprobane acquired a fourth owner.

A member of parliament, P. L. Jinadasa had it for a short time. He cut down a tree or two that enabled those on the mainland to have a better view of the house that by then was painted white.

Paul Bowles, the American writer and composer was the fifth owner. A young Arab companion, a competent painter, accompanied him and it is said of him that after eating hashish he painted unintelligible daubs, very way out paintings indeed. They found it difficult to settle on the island. Knowing nothing of the language they were unsuccessful in making friends with the locals. The distribution of the hashish ‘jam’ to win popularity served only to themselves very unpopular. The fisher folk of Weligama took an intense dislike to the American and his friend Yakoubi. The more they tried to win popularity the more unpleasant the villagers became. In fact they made their life hell, hooting and whistling and showering the island with rocks and stones, particularly after dark. Bowles and Yakoubi became disenchanted with the island and moved to the New Oriental Hotel in Galle. The place was put up for sale. Paul Bowles thought the furniture he had bought with the house was valuable antique. He approached Bevis Bawa for an opinion and valuation. When Bevis Bawa turned up he found little of the original furniture he had known so well in de Mauny’s time. After use by four owners much of the de Mauny pieces had either been removed or replaced with mundane furniture. In fact with the ravages of time and numerous monsoons even the few de Mauny pieces of furniture were then of little value.

The editor of the Illustrated Weekly of India, Shaun Mandy, was the next unhappy owner. He had hoped for perfect peace and quiet in the solitude of the tiny island to write a couple of books. He managed to get half way through one with people pestering him the while when he had harsh words with the then Minister of Finance. He left in a hurry, selling the place to yet a seventh owner who I know not what of.

Robin Maugham writing in his ” Search for Nirvana ” recounts how he visited Taprobane in the early seventies and decided after much soul searching that the place in its then derelict state would be too expensive to rehabilitate, and even more damning, the location had lost its original charm.

As I stood there recalling the history of Taprobane my mind raced over the various people who had lived there; their aspirations, their hopes and their eventual disappointments. What is it that many of us are looking for? What am I doing in Ceylon? Maugham was searching for his Nirvana when he last came here. He never found it before he died in Brighton. Why is it many look for this ideal when we are nearing the end of our sojourn on Earth? Do we hope to repeat experiences we enjoyed in our earlier years if only our diminishing vigour would allow? I cast my mind back to fourteen years of happiness in my little Arab house with my very private family. The years spent in Algarve were pleasant but perhaps wasted, followed by the last seven happy years in Europe. What am I looking for? What shall ……….

“Seen enough” called Robert.

“Yes, I don’t suppose we stand much chance of looking over it”. I replied, my thoughts broken into. ” We had best push on, we are not making much mileage – it will soon be lunchtime”.

We reached Matara in time for lunch at the Rest House by the seashore across the bridge over the Nilwala river. Large bottles of ice-cold beer and Fanta ice drinks for the lads helped quench our thirst before the welcome curry lunch. It was too late to see the Star Fort as the driver agreed, he recommended pushing on to Tangalla but he grumbled and said we should have seen the Weurukannala Vihara temple just a short turn off from the town of Dikwella towards Beliatta. There, built twelve years ago, is a giant statue of Buddha fifty metres high. Put to the vote the boys and Robert were keen, the driver too, although he had been there on several occasions, so we went. It was a quick visit. We parked the car as near as we could to the entrance, as we had to discard our shoes. Robert and I kept our socks on which rather defeated the object of not defiling the temple with the dirt carried on our feet from outside for we had to walk across twenty yards of loose sand and I suppose to be scrupulous we should have taken off our socks. No one challenged us. The original temple is about two hundred and fifty years old. There is very little to see. The second shrine has a collection of life size figures painted in vibrant colours depicting the life and times of Buddha, in his infancy, on leaving his family to seek enlightenment, the finding of it, preaching the message and in the end achieving Nirvana. There are numerous other paintings of Buddha in previous incarnations standing, seated and reclining. Together with models of monsters, devils and other figures the collection is so gaudy and prolific as to be overwhelming. I was pleased to be outside looking up at the huge concrete and plaster figure of Buddha. It all seemed too new and commercialised to me. Buses and cars filled the area around the temple with tourists swarming everywhere to gaze at this tall concrete building backing an enormous stylised brick and concrete figure.

Why didn’t I appreciate it? Tourists, why call them tourists when they are mostly Lankan nationals, would not a better name be “pilgrims? And why do I, in particular, revere only ancient buildings and monuments and shun the modern. Should not religion of whatever belief keep itself up to date? Did my formative years as a conscripted Christian teach me to think, or perhaps lead me to think and expect religious buildings to be at least one thousand years old? At first sight I had rejected the new Coventry Cathedral as a suitable building, it had to grow on me gradually. I have yet to accept the brick and angular wooden structures built as local churches in the middle sixties. As for gaudy colour, I remember how I recoiled with shock when first viewing Graham Sutherland’s backcloth in Coventry Cathedral. John Piper’s cartoon strips backing the altar at Chichester do nothing to inspire me. One can only say they give a touch of colour. His work and style I never liked.

So why should the garish comic strip method of painting in a Buddhist temple upset me? Perhaps it offends my sense of repose and the serenity I associate with Buddha.

As we reached the main road Robert started to study the road map and after a while came up with the information that we had passed the southernmost tip of Sri Lanka, Dondra Head some few miles back. It pleased me to know he was taking an intelligent interest in the journey, but my mind dwelt on other matters; the state of the road and the slow progress. The road was in a very dilapidated state. Ratnapala slowed his speed concentrating on missing as many potholes as he could. It was around four o’clock when we reached Tangalla.

The Rest House is a very old and attractive building situated in the middle of the small town, reached along a narrow road. The Dutch built it in 1774. One can sit on the wide veranda gazing at a stretch of silvery white sand on the east side. Looking west one sees white crested waves gently pounding the shores of the small bays which form a perfect backdrop for the harbour sprinkled with small yachts and gaily painted fishing boats. In the few minutes whilst waiting for the tea to arrive I recalled a similar scene fifteen years ago in a village at Cape St. Vincent near Sagres in Algarve.

Robert had been talking with the head waiter and was to inspect the rooms because if we could not reach Tissamaharama before nightfall we would have to stay in Tangalla. I joined him but we were not impressed with the standard of the rooms and toilet accommodation and, as the driver had assured we would reach Tissa before dark we decided to press on.

The road surface became worse, in fact it became downright awful. We were all a little tired; when we approached Hambantota the sun was lowering on the horizon. The scenery changed, we were passing through scrubland, and the coconut groves and rubber and banana trees were no longer in evidence. The road was passing along the edge of the Bundala Sanctuary and this made us a little more alive and appreciative of the journey. The shadows lengthened and the potholes seemed deeper and more numerous. A light rain fell and the twilight turned to night as we drove across the bunded road over the Tissawawa Tank and into the Tissa Rest House.

Our first impression of the hotel was a large open foyer with a smartly tiled floor. Several staff worked behind the long reception counter with an impressive executive type hovering in the background. Half a dozen bearers were dodging about carrying suitcases and baggage. Most buildings have a different atmosphere by night than one finds in the cold light of day. The interior of the Rest House was no exception. The main accommodation block fronted on to the placid waters of the Tank with the service blocks to the rear connected by a high ridged roof supported by heavy wooden columns fashioned from almost perfectly rounded coconut trees polished to a mirror finish. Underneath were housed the various service areas on open plan each raised about twenty inches above the walkways and at suitable intervals steps connected one’s progress. The floors and walkways were finished in highly polished dark red concrete in which the ceiling lights were reflected. This proved a hazard for me. Twice that evening I almost stepped into space when moving from one area to another.

As prearranged Robert was to negotiate the room bookings and the usual signing in and all the attendant details. Standing around feeling I ought to make myself useful I mentioned to Robert in the midst of all the bustle that the driver and his accommodation be looked after. I should have known better. In a slightly strained voice he said:

“Let me organise the rooms, luggage and the driver, why don’t you go to the bar and order some drinks – I’ll be along shortly”, and as a parting shot he hissed in a whisper: “Don’t fuss! “

After dinner Jayantha and Ariyadasa were off to enjoy the plumbing and the ambience of their room for this was the first time they had stayed in a hotel of this size and quality. Robert and I wandered into the bar area. Ordering our second drinks we moved across to another of the raised areas near to the foyer and settled in very comfortable wooden framed chairs with wide leather latticed seats.

It was at this point he appeared. I thought he was the manager of the hotel. I had noticed him earlier talking with one of the guests at the reception office.

“Good evening gentlemen, I hope you enjoyed your dinner”. He was well built, above average weight for a Sri Lankan, good looking, well groomed and neatly dressed, articulate and full of confidence.

Half an hour later when he had gone Robert asked in a dazed way, “Did we do right; have we made the right decision?”

“Oh, I think so” I replied, “Anyway we can’t go wrong it’s a hotel sponsored trip and he given us twenty per cent discount – our problem now is organising someone to make sure we get our breakfast at four-thirty in the morning.”

For our friend had persuaded us not to take our car out to Yala and, as he expressed it, “become just another tourist and join a bus load of them packed tight in a mini bus and be driven around on a scheduled circuit”. We had hired one of his safari jeeps for the same price it would cost the four of us to go on the scheduled tour. He would provide a fully equipped jeep with driver and guide. In fact he knocked off twenty per cent – this after some time when he felt we were not keen to take up his offer. He was so convincing, never at a loss for an answer, whichever way we both assailed his patter with queries, always ready to assure us we would be well satisfied with his tour, as had many thousands of his previous clients over the years. Indeed he had three other Jeeps going out on similar trips in the morning.

As we walked along the veranda to the bedrooms Robert asked:

“I suppose this trip is to Yalta Game Park and not to some other place he knows of?” The same idea was in my mind but to avoid a long discussion on the possibility, and in order we could get some sleep in the few hours that remained, I countered with:

“Well, he did say we would see more than by going in a mini bus, and the jeep can go places they can’t get to and anyway, we are booked, we shall have to wait and see.”

Sleep came easily; a splendid supper washed down with several beers had done the trick. No sooner had my head hit the pillow than the room boy was announcing tea. Robert and the boys were already milling around outside going down to the dining room for simple sandwiches.

It was five o’clock by the time we piled into the veteran Jeep. A sturdy roll bar, heavy iron girder bumpers, extra grills and a rather battered tubular framework for the tilt gave it a safari authenticity. We turned right outside the Rest House gates. Perhaps there was another route but it was too early in the morning for intensified argument. However as we reached the bunded road crossing the Tank I yelled above the noise of the clattering diesel engine to Robert sitting with the others in the back.

“Ask him where we are going! “ After a long dialogue I learnt we were going to collect the guide. In the distance a breakdown lorry loomed out of the morning mist seeming to fill the whole width of the narrow bunded road. The Jeep was left hand driven and I felt very exposed in the right hand passenger seat facing oncoming traffic that observes the rule of the left hand side. I held my breath. The two vehicles stopped alongside each other with three inches to spare between them. The driver leaned across me and held a staccato chat with the driver of the truck. The first light of dawn appeared, the sun would soon be on the horizon and still they chattered. At last we started at which point the guide who had been slumbering in the truck leapt out and chased after the now speeding Jeep, to be hauled on board by Aryiadasa to raucous banter from the driver.

The Jeep swung off to the left following the main road. I missed reading the signpost busily hanging on to the Jeep superstructure to prevent being tossed out. Although the vehicle was travelling at only twenty miles an hour we bounced in the air at every pothole. Suddenly I recognised the road. We were heading for the Bundala Wildlife Sanctuary. In reply to my query:

“Robert do you remember this road?” he replied with an English expletive and started a heated dialogue with the driver who drove on relentlessly. I understood not a word of the Singhalese conversation but from the inflection of their voices I was not surprised when the driver slammed to a halt. He started to turn the Jeep around. I cried:

“Stop! What goes on?” He said in English:

“Go back Tissa!”

“Just a minute,” said I addressing Robert, “I know we are on the way to Bundala but if we go back now it will be too late to go to Yala and we shan’t see anything – anywhere. If we push on now we shall have a chance of seeing some game – and we shall be charged for the trip if we turn back, so we may as well go on”.

“Oh no we won’t, I’ll not pay him a rupee ” said Robert with much anger. When in this mood a little guile is needed to get the right answer.

“O.K. then is you think we should, we go back, but Jayanta and Aryiadasa will be disappointed and so will I, we shall have wasted our time and if we return without seeing anything we shall feel and look very stupid”. With the ball firmly in his court Robert did as I expected him to do, a quick volte-face.

“If you think we should go on to Bundala that’s your decision!” placing the onus smartly on me.

“O.K. then – let’s go”, and so saying I tapped the metal windshield and pointed down the road.

We shot off in the direction of Bundala. I turned to smile at Robert; he looked fixedly ahead towards the now pink horizon.

By the time we reached the sanctuary the sun was lighting up the day. Scrub and thorny brushwood towering above the jeep was getting progressively thicker as the road turned into a narrowing sandy track. Paths criss-crossed at all angles and after about a mile or so the guide leapt out, the driver stopped the Jeep and followed him. They were back in a minute having decided an elephant had crossed the track at this point. On we went, the vehicle bucking and bouncing as the track turned into a swampy slide. Left turns, right turns, so we careered onwards. Torn at by thorn and scrub, heads down to avoid the thud, bumped and bruised we hung on tightly, we crashed on, turning and twisting. At last we pulled up. The guide and the driver pounced on a couple of elephant turds the size of cannon balls. The guide kicked them with his foot; they both inspected them for freshness. To me the turds looked new, but not that new. Fresh, they should have emitted a certain discernable heat; they did not. The guide’s excitement seemed rehearsed and as he trotted off down the nearest path we made to follow. The driver said:

“No go, stay, me go”, and went off after the guide. They returned almost immediately and reported to Robert that an elephant had been there but had since gone on.

“This morning or last night?” I said, addressing my remarks to no one in particular but as only Robert understood what I had said and as he was busy asking questions of the guide, my remark fell flat.

We made several elephant sorties and at the third sighting whilst everybody was absorbed in inspection of elephant droppings I wandered off back up the track to water the daisies. Thus engaged I realised I was being observed by a rather large monkey in a tall tree a few yards away. I looked around to see if there were any more of the family but none appeared. He was still there, higher up the tree as I turned to join the others. “I’ve just seen a monkey over there in that tree.” The two boys ran off to see for themselves but their noisy approach frightened it away for they didn’t believe me.

We went elsewhere to search for elephants, bouncing down tracks overgrown with thorn bushes that scraped and pounded the vehicle from all sides. The clatter of the engine and the commotion we caused must have scared everything away for we saw no game animals. The jungle began to thin out into scrubland and we were faced with gullies and hillocks and unexpected hidden ditches. The rains had caused havoc in this part of the land and the Jeep swung and crashed at alarming angles. Rounding a small clump of bushes we slithered into a bed of wet clay at the bottom of a deep gully. The driver’s reaction was immediate; he slammed the engine into low gear and charged up the side of the gully at full speed. Wheels spun, mud flew, and the Jeep almost stood on its tail. The angle of attack was so acute it should have succumbed to the law of gravity; instead the wheels clawed and dug at the side of the wadi whilst we clung on praying the driver’s nerve did not fail him. He had the sense not to stop when we reached the top but to continue for a hundred yards at respectable speed to allow us all to regain our composure.

We all got down, the driver to inspect his Jeep, the rest of us to stretch our legs. It was the umpteenth time I had swung my legs down and back jumping in and out of the Jeep. It was a bit like the Western Desert, Sidi Barrani and Gazala way back in forty-one, except I was a damn sight more agile then. Even so, I was enjoying the ride although we were seeing few animals.

Before us in the middle distance was a herd of water buffalo. The morning mist lay lightly in gossamer wisps. The keen clean air was tinged with an aroma of the herd most of them recumbent, a few now stirring. For some reason the driver took delight in driving amongst them, revving and weaving the Jeep. He seemed oblivious of the look of distaste I turned on him. When we ran over the tail of one magnificent beast that refused to move and glared at the metal monster spoiling the start of his day I pointed to the flamingos and cranes at the edge of the lake and suggested we look them over. It was whilst photographing the bird life that we discovered the top half of the camera case was missing. It must have shot overboard in the hectic journey. There seemed little chance of finding it, a camera case in the jungle equates to the proverbial needle in the haystack.

Driving around the edge of the lake the crew decided to rest and enjoy a cigarette. Twenty yards from the edge of the water a small island rose, flat and barren a couple of feet above the surface. Talking through his cigarette the driver said in English:

‘”Crocodile” pointing to a sodden bit of old tree trunk lying half out of the water on the edge of the island.

“Where?” said Jayantha, although he spoke in his own language it was obvious what he said.

“There'” answered the driver, pointing to the log. Jayantha, Robert and I were unconvinced. Only Aryiadasa dissented. He produced his powerful lensed spectacles, which he is supposed constantly to wear and agreed it was a crocodile. The guide picked up a short stout branch and flung it with vigour but it fell short making only large ripples – he claimed he had seen it move. Jayanta a fan of Kepal Dev, picked up a large lump of sandstone and taking a short run with a powerful arc managed to hit the end of the log lying on land. The log began to sink. Everyone joined in with a fusillade of sticks and rocks. This proved too much for the ‘log’ that swam off at great speed.

“So far we have seen only elephant crap and the tail end of a crocodile”, grumbled Robert in the anticlimax of the sortie. “What do we do next?” he enquired, announcing as an indictment “It’s gone seven o’clock”.

‘”Well it’s up to the guide and the driver,” said I, “Get cracking on them.”

We bucked and bounded westward deeper into the scrub and back once more into the jungle. The land was scarred with wadis and paths that had eroded away in the heavy rains. Bouncing down a narrow path, both sides of the Jeep scraping the wickedly brutal lashing thorn bush we came to an abrupt halt. The path had disappeared. It had fallen five feet, washed away by heavy flooding rains. We backed off, fearful of our arms and faces being cut to ribbons as the Jeep reversed at speed. We spent a long time finding our way out of the maze of jungle paths.

Many wide detours were made only to arrive back in the same area. Time was passing and there now seemed little chance of seeing any of the early morning animals we had hoped to see.

Rounding a corner we came radiator to radiator with another safari wagon conducting two German tourists from the Rest House. Their driver backed off with us following, and, at a suitable point both trucks drew level and the crews compared notes. As we were about to move off the driver of the other safari wagon produced a camera case lid he had found about an hour previously when following our route. Robert was overjoyed to get it back and when shaking hands he passed over a respectable size currency note.

A little later we came upon a troupe of largish monkeys, about ten of them, they were difficult to count as they were swinging all over the place but they sped away as soon as we started to get down from the vehicle. The best sight of the morning was the magnificent peacocks and peahens. There were hundreds of them and to make up for the lack of sightings the driver drove around for fifteen minutes stirring up dozens of them and encouraging me to take photographs. Just my luck, the film ran out.

Around nine o’clock we headed for the Rest House at Tissamaharama.

By the time we arrived I was well conditioned for the bumpy rides in the week ahead. Robert was quiet on the return journey, other than he asked me more than once if I had enjoyed the trip and thought it worthwhile. To be honest, I had to say that I would have preferred going to Yala but on balance I had thoroughly enjoyed the Bundala trip, and, no, I wasn’t worn out, tired, yes, and no I didn’t think we had wasted our money. This did not prevent him from having the most awful row with the safari man back at the Rest House. I didn’t see it. I learnt of it only when he came back to the bar after paying him off.

It was time to get on with the journey to the hills. Bags packed, bills paid and a steady start on the road to Wellawaya. We reached the Rest House at Wellawaya in time for a late lunch. We were the only guests and the staff seemed surprised to see us. The lunch was simple, ample and cheap, costing less for four curry meals than the beers and Fanta we drank.

I had heard a great deal about Ella Rest House from my planter friends and Robert who had visited it in the years gone by was determined we would stay there for the night. We rolled up the steep hill to the Rest House at four o’clock. We were out of luck, every room had been taken. The disappointment showed on Robert’s face and I could understand why. The Ella Rest House was a gem of a place. The view from the terrace was breath taking, and would have been the more so had we have seen it earlier in the day, particularly in the early morning light. The building was designed with the bedrooms below the restaurant and service rooms, built into the side of the hill. The servants seemed particularly smart, personable and cheerful and seemed genuinely sorry they couldn’t provide rooms for us. We settled for a pleasant tea and were sorry to leave.

It was but a short ride to Bandarawela. A pleasant town, two good hotels a Rest House and several smaller guesthouses. We settled for the smaller and less expensive Orient Hotel. The rooms were clean and spacious. The plumbing, as in all tourist hotels, suspect, and guests needed d.i.y. experience. The lounge was empty, as was the bar. We were the only guests. It was pleasant and the boys liked the town; there was a cinema showing films they had missed elsewhere. It suited me to agree to stay for two nights, as I needed walking, exercise and a rest from sitting most of the day in a car. And the bill was not going to be too large for I was to be charged full tariff whilst Robert and his nephews were on half tariff with the driver on a token charge. Not a bad arrangement. In fact the boys ate out much of the time as they enjoyed being free in the town. After dinner they found a karem board in the lounge and settled for several games. I frequented the well stocked bar with the barman for conversational company, sampling the local gins as a change from the arrack. Reading the hotel brochure I discovered there was a billiards and snooker table listed under recreation facilities. The barman seemed less than helpful when I asked him if one could arrange a game. The room was locked up. The hotel owner or the manager was not available. It all seemed too much trouble.

The second night returning from an early dinner I walked into the older part of the hotel and found several people in the billiards room. The owner’s son and a couple of his sycophantic friends were playing a form of snooker I didn’t recognise; they seemed to make the rules as they went along. I sat and watched them play. The lady owner came in and seemed slightly surprised to see me although she did come and sit by me; I was sitting on the only available settee in the room. She was not unattractive, buxom, about fifty or so, happy to talk about her precocious son who had studied law in London – they had relatives in Croydon who also kept a hotel.

“Oh yes, one had to be so careful about the table it cost such a lot of money.” She had bought it primarily for the son to keep him amused, but “To let hotel guests play on it was not wise, they treat it so badly you know.” Perhaps they do, but it seemed a bit cheeky to advertise it so blatantly in the hotel brochure and then lock it away.

Passing through the small reception lounge I noticed the antique furniture was very ornate and beautifully carved and the grand piano looked a magnificent instrument until one lifted the lid and tested the keys. It couldn’t have been played for years. This part of the hotel must have been the original private house, now forming part of the public rooms for the hotel extension built more recently. One gained the impression the hotel was run as a private home.

I could not complain about the waiter service. Being late down for breakfast I ate alone. Two young waiters vied with each other to serve me. In fact they hovered around the table making me uncomfortable until I found they wanted only to ask for advice on how to get a job in the Arabian Gulf. Waiters earned much money in Arabia and if the Mahatihir could give them a letter they stood a good chance. This was an opportunity for me to learn how much they were being paid by the hotel. This turned out to be three hundred and seventy five rupees a month and their board. At the present exchange rate just under ten pounds and the food.

The Dunhinda Falls had been marked as a place of interest for all of us. Aryiadasa was particularly keen to see them. The water falls in a huge torrent almost two hundred feet. It lay some four miles beyond Badulla about twenty miles to the North East of Bandarawela.

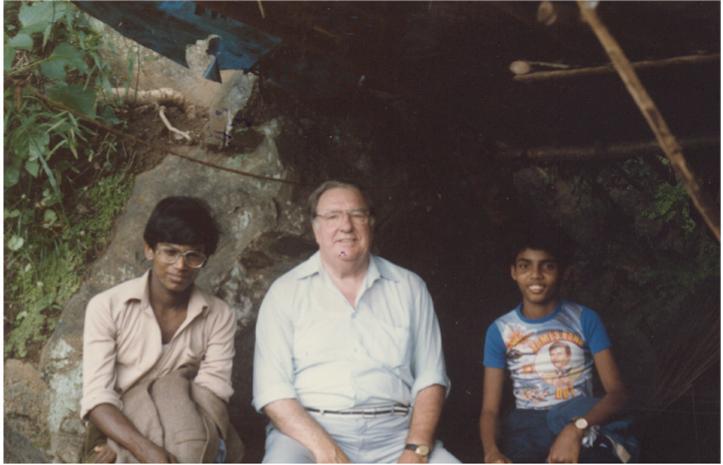

We piled into the car and wended our way along the road to Badulla stopping after a few miles to visit the Dowa Shrine. One has to descend many steps to reach this delightful little temple built near a cave in the side of the hill. The cave had been the refuge for a legendary king fleeing from his enemies and the shrine was built in commemoration. The rock face has a handsome low relief figure of a standing Buddha about fifteen feet high.

Badulla town was, by general consent, the nicest town we had so far seen. It was so clean, the shops were so tidy, so well laid out with merchandise marked with prices that were very competitive, considering it had to be hauled so many miles over such atrocious roads. We were so delighted with such neatness and cleanliness that we had to resist our impulse to random buying. Robert suggested it was the clean air and the cool climate that engendered a sense of purpose and pride in the shopkeepers. I agreed, and added that perhaps the fact that there was no dry fish on sale anywhere, also helped.

Our sense of well being was rewarded by the many dishes and huge helpings we were given for lunch at the Badulla Rest House. Thus fed we made our way by car to the Dunhinda Waterfall.

Ratnapala drove with care. He was worried about the huge potholes and the punishment the tyres were taking. The winding twisting road cut into the side if the hills finished abruptly. A line of shacks and tiny shops blocked the end of the road that had been widened into a viewing platform guarded by a low cement wall. One obtained a marvellous view of the tea estate country.

One bright lad from the crowd of local youths who were waiting for a chance to act as guide and mentor offered his services and came along. The way to the falls was down a path off to the right, a walk of almost two miles. We trouped off past the shacks and little shops along a winding path through tatty gardens and dusty brick and wattle huts which housed the people who ground out a living from the tourists visiting the falls. The path became less wide. It cut deeper into the side of the hill. It ran up and it ran down. Long slabs of smooth rock gave way to large boulders. The path narrowed alarmingly as my right arm brushed the face of the cliff. I looked over my left shoulder into the trees and blue sky and scudding clouds. Looking down at my feet I caught a glance of the tops of thick bushes that I realised were actually the tops of trees growing much lower down the hillside. As the path wound its way around the cliff face I saw ahead a hazard I had dreaded. A slab of rock about twelve feet long and less than two feet wide bridged a drop of a hundred feet. I stopped to admire the view. Robert knew I suffered from vertigo. I hated to admit this before the driver and the boys. They had gone on, Robert stayed back.

“Shall I go first?” he said, “Come on take it slowly”.

“It’s quite all right,” said I with more confidence than I felt, and walked forward as to a scaffold.

Of course it was easy, remember just look straight ahead and don’t look down. The local youth posing as a guide wasn’t fooled, he would have seen this fear of heights before and he hung back to lend a hand. He was useful in helping to steady my bulk over large boulders and rocks that blocked the little path cut out of the hillside. About half way to the falls it was obvious my slow progress was irksome to the lads so I told them to go ahead. They skipped along like mountain goats whilst I stopped to rest, Robert and the local lad hanging back. We went on a short way until the path became much worse and I was being hauled and guided over wet rocks until Robert said:

“This lad tells me the path gets even worse as we go further down – do you think you can make it?

“To be honest, not in comfort” was my reply. “I think I should stay here, you go on with the lad and I’ll just rest”.

“O.K.”. he replied, “If you think you’ll be alright I’ll go on down but let this fellow stay here with you – he says it shouldn’t take me long.”

“Remember the spirit of the British Empire! Don’t give up! Don’t let the side down! Even old ladies walk down to the waterfall. You must carry on”. I couldn’t believe my ears. If he had not shut up and moved on I’m sure I could have gladly clocked him and chucked him over the edge. By the time the rest of the party returned from viewing the falls I was rested and in better humour. The walk back to the car was uneventful other than the stop we made at a little shack where Robert bought us each a cup of herbal tea, which tasted delicious.We had been resting there about five minutes when two men came by returning from seeing the waterfall. One was a local, about thirty years old the other a Muslim, almost Pakistani in appearance. They stopped to say hello, and asked the local lad what the trouble was. I couldn’t know what he told them but he must have said I had lost courage for the heavier of the two regaled me, in broken English to:

Just before we reached Bandarawela, driving past the Dowa Temple climbing up a gentle hill when the nearside back tyre blew. We rolled to a stop and all piled out to see the damage. Ratnapala was not dismayed. Off came the wheel and shredded tyre and on went the spare from the boot. The tyre on the spare was almost as bad as the one taken off. It had been roughly patched and looked as though it would disintegrate at any moment yet he assured us it would carry us safely back to the hotel.

The following morning the driver reported he couldn’t find a suitable tyre to buy. He suggested maybe when we reached Nuwara Elyia he could buy one there. I didn’t like the idea of driving all that way on a duff tyre, but there seemed little else one could suggest. We drove on. At first the road was reasonably good but as we climbed higher in the mist the road became worse and deteriorated into a series of potholes connected by tattered pieces of tarmacadam and even that combination petered out to become a rutted sandy track. A slow bumpy grind up to four thousand feet. My mind dwelt on the state of the tyres. The two on the front were, by Sri Lankan standards in fairly good shape whilst the offside back tyre had long ago passed being safe and we all knew that the spare tyre now on the nearside wheel could blow out any time.

Ratnapala drove carefully, I realised he understood the risk we were all taking. The car was heavily loaded, indeed, overloaded but one had to grin and look cheerful even if one had quite different feelings.

A heavy mist hung over the botanical gardens at Hakgala. We were able to inspect the attractive layout but the misty rain prevented us from viewing the place at it’s best. It was obviously very well kept and we traversed as much of it as the conditions permitted. The rose garden was said to be worth seeing, the few blooms on the many bushes led one to think they had been pilfered. How else could the bushes be so bare? I was able to photograph a solitary yellow rose the petals heavy with dew, a beautiful picture.

The road climbed higher and higher, getting worse. In some places it was only an earthen track. There was evidence that recent rock falls had taken place, the potted road surface was strewn with large and small rocks washed away by the rains from the overhanging rock face. It was not an enjoyable ride knowing that the back tyre was bare of rubber tread and with relief we began to descend the last few miles into Nuwara Eliya. The mist cleared and passing a few wayside dwellings near Margastotte it was interesting to see bunches of beautiful roses for sale.

Our rooms at the Rest House in Nuwara Eliya overlooked the racecourse. They were palatial with commodious bathrooms attached. The hot water system worked very well so long as the electricity was switched on. We were now at more than five thousand feet and a hot shower was not only luxurious but also essential. It seemed the floor waiter had instructions to remove the fuse controlling the circuit for the hot water boilers in each bathroom and to connect up it each morning at a certain time or if requested. The last bit he didn’t seem to understand. I had make loud noises to convince him I was intent on having hot water as and when required. Otherwise we were comfortable and the dining room service and food were adequate. Though not the best accommodation available in Nuwara Eliya it was clean and inexpensive.

Robert introduced me to Christopher Worthington who came to Ceylon as a planter. He stayed on after the tea estates were taken over by the Sri Lankan government and lived privately in Kandy. He moved a few years ago to Nuwara Eliya and kept himself and his servants busy and self-sufficient on a small farm up the hill towards Margastotte.

We drove out to his place at Bakers Farm for tea the next day. He rented a bungalow built in the style of the English thirties perched neatly on a knoll looking down on to Nuwara Eliya with a backdrop of the mountains in the distance. It was not easy to drive up to the house, as the drive seemed so very steep. It was filled with comfortable furniture and choice pieces of memorabilia, expensive oriental rugs and well-polished items of silver complemented by a catholic collection of water and oil paintings. It seemed too much for the bungalow, as though all the family heirlooms had been brought there. Christopher sensed I responded to good pieces. When I remarked he had a small treasure house he told me that not all had been in the family. One or two choice items and pictures had been obtained from redundant tea planters and other Europeans long since gone from the land.

The nostalgia was overwhelming. One felt transposed not only to England and an English bungalow but back in time to the days of tea and cucumber sandwiches and Noel Coward.

Next evening Christopher, Robert and I had dinner at the Hill Club. On entering the building here too, one is filled with nostalgia. It is like being back in the English colonial era between the wars. The club was developed from the original billiards room built in 1876. The walls of most rooms were decorated either with pictures or trophies of bygone times. The original furniture and fittings, the notice boards, the name boards to the various rooms, the vases, the brasses looked well kept and polished as they have looked for more than a hundred years. The servants reflected the old disciplines and customs. I had never before been in the Hill Club, yet it took me back in time because I had been in establishments in India and Egypt that were quite similar.

In its heyday it was de rigueur for members to wear proper dress particularly in the evening. Nowadays trousers and sports jacket are acceptable provided one wears a tie. To survive financially the Club has become an upmarket tourist haven. Its twenty-two rooms are invariably booked months ahead.

We moved on to the Golf Club almost next door for after dinner drinks of several large brandies. We were the only three Europeans in the club bar – the only part open at that hour – there were five rather sloshed Sri Lankans who switched into English when we walked in. This is something I have noticed about the Singhalese. They are very polite and when one is there they will converse much of the time in English. Not so the Tamils, they seem to chatter away oblivious of others not understanding them. Which, of course is their prerogative and right.

It was pleasant to wear a suit again and still feel cool; indeed on going to bed I switched on the tiny electric fire and pulled it to the middle of the room to take off the midnight chill.

The next morning Ratnapala reported he had been able to buy a re-treaded tyre for three hundred and fifty rupees so we all felt safer even on a retread.

Our departure from Nuwara Eliya was delayed by a petrol crisis. There was none to be had at the three service stations. The driver said there would be enough to get us over the mountain road and on to the next service station. On we went, everyone looking out for the next petrol station. Of course, we went for miles crawling inexorably up and down the mountain road and didn’t find one. The down bits were a bonus. Ratnapala switched off the engine and used his brakes until I objected when the brakes began to fade. Our apprehension of running out of petrol was offset by an amusing feat by one lad who ran like a gazelle. Driving past a group of houses overlooking a valley some lads tried to sell us bunches of flowers. As we drove round and down the series of steep bends one boy who had been more persistent appeared at the next straight piece of road. We drove on, the same thing happened. He appeared like the genie out of the bottle. The third time it happened we realised he was chasing down through gardens of the houses. When we met the for the fourth time we gave him a small reward of two rupees, which of course was the reason for the chase.

We began to descend but Kandy was many miles away, we had to have petrol soon. A large sign “Labookelle Tea Estate” above a wide gateway came into view. The driver thought we should try our luck here. As we drove up to the office Robert suggested we use Duncan’s name. Duncan Scobie a friend of ours had been a tea planter in years gone by. The superintendent, Mr. Samarasinghe on hearing our problem was able to help us – he joked about our buying plenty of packets of tea from the tourist shop and they would sell us petrol to get us to Kandy. It was then we mentioned Duncan’s name. He wished to be remembered to him and asked if he still played Rugby football; Samarasinghe and Duncan had been rugger buddies. We were shown over the factory, which was a good educational exercise for me and for the two boys. When we reached Gumpola we took on petrol to fill the tank.

The Peradeniya Rest House near the Peradeniya Botanical Gardens just a few miles before reaching Kandy seemed to be a good place to stop eat and make plans. The curries were excellent, perhaps too hot, everyone thought so, and most enjoyable for we ordered more beers and Fantas to slake our thirsts. The botanical gardens cover about one hundred and fifty acres and are situated in a loop of the Mahaweli River. We were allowed to take the car through the gates and it was certainly needed.

The roads through the gardens go on for miles and one can enjoy a collection of trees, plants and so fine and wide a variety of fauna to put Kew Gardens in the shade.

We could not make up our minds where to stay. The Tourist Office seemed a good idea and after misreading the map we eventually found it. They were most helpful, gave us several addresses of suitable hotels and larger pensions and sent us on our way. The trouble was we lost our way, yet again, and after several visits to quite unsuitable places I felt somewhat weary and looked forward to a shower and a cool drink. Robert was chatting away to his nephews and I found it difficult to capture his attention.

“Look, we must decide on a hotel – or we shall be camping out tonight!” No response. “Robert! You have the guide book, please choose a suitable hotel”.

“O.K. keep cool”, said Robert, and he chose a hotel which was way above the budget we had agreed. When I demurred, his reply:

“Well I stayed there when Duncan and I were last in Kandy” infuriated me beyond reason.

“To hell with Duncan!” was my repost. This shook the lads, even though they didn’t understand fully the conversation. But it brought response from Roberto. He instructed Ratnapala to take us to the Thi Lanka Hotel.

The Thi Lanka is situated on the hills high above the Temple of the Tooth. One turns left off the Anagarika Dhamapala Mawatha Road and climbs steeply to find the hotel hidden in the trees, yet with fine views and fresh cool breezes. Although this was a good class hotel the maestro was able to arrange very good terms for the rooms and the food and even talk them into providing room and board for Ratnapala, the driver. After wallowing in a hot shower I was in better mood and soon Robert and I were enjoying long cool drinks at the bar. The boys had gone exploring in the town.

We had not quite finished dinner when the driver appeared on the veranda; Robert beckoned him to the table and asked what the trouble was. No trouble, only good news, did we wish to see the Kandy Dancers? If we did he would go and book seats for the four of us; the Casino was only two hundred yards up the hill.

As it was raining it was decided we would go in the car and it was well we did so, for the steep track up to the Casino was ankle deep in mud and it was with difficulty that Ratnapala delivered us to the door. He had already been talking to the man on the ticket desk. We paid in full, the two lads got in for half price and of course, the driver went in for free.

The show was fabulously colourful, talented, well presented and incredibly noisy, the clashing cymbals and recorded trumpets were all so well co-ordinated that one was carried away with the dancing and the acting.

The opening number entitled “Magul Bera” was the traditional invocation. Customary ritual music to seek the blessings of the guardian deities. This was followed by the “Puja Natuma” dedicating the skills of the Kandyan dancers to the deities of the land. Next followed a folk dance, known as ” Devol Natuma ” a vigorous dance performed to ward off evil influence and also for healing specific ailments. The sequence was derived from the dance forms of the southern parts of Sri Lanka. The Peacock Dance or the “Mayura Vannama” was very graceful. In mythology this bird transports the God Skanda of South Ceylon and is worshipped both by Buddists and Hindus. The tambourine dance “Pantheru Natuma ” a lively number accompanied by dexterous drummers was followed by the famous Devil Dance of the south province, the ” Raksha Natuma “. The heavy masks worn by these particular performers were whisked around on their heads with great ferocity and skill. The dance is performed in south Ceylon to exorcise demons and is still believed to be an effective psychiatric treatment.

In the interval, Jayantha and Aryiadasa chatted like young monkeys. They were so impressed never having seen anything before in their lives to compare with this. Coming from the southern part of the country, from “Yakha” country they were not unaware of devil dances performed in their villages. But this performance was being presented with great skill and occasion.

The “Lee Keli Natuma” or Stick Dance opened the second half. This was followed by the “Raban” a traditional folk dance extolling the art of playing the Raban, a drum like instrument about one foot in diameter held with one hand and played by the other with plenty of vocal accompaniment. The fire eating dancers performing the “Gini Sisila” showed the power of charms over fire.

The main piece of the evening was the “Ves Natuma “. Ves is the traditional dress of the Kandyan dancer. Sixty-four ornaments complete the dress. The dance is considered the most important in the Kandyan form with years of rigorous training taken before a dancer achieves the status of a fully-fledged ves dancer.

The pretty damsels performing the Harvest Dance were most graceful and were a delight before the finale of the Drum Orchestra and company.

It was late in the evening when we returned to the hotel, the boys went off to bed and Robert and I chatted together in the bar. There was some discussion with the barman who was charging us varying prices for the arracks we ordered. When we could not reconcile the differences the barman called in the manager. When we arrived earlier in the day he had not been in the hotel. Now he and Robert greeted each other like old friends, they both came from the same village. The result being we still paid the different prices for the various brands of arrack we drank but we were given thirty per cent discount. I think, much to the chagrin of the barman.

As I lay reading in bed I wished we could stay on longer this trip. I had to get back to Colombo to arrange for an extension visa, which had to be done in three days time. This meant we must make the most of the morrow.

Kandy is, indeed, a romantic paradise. Forty years ago after six years of war service I had to make a decision, either to accept repatriation to civilian life in the U.K. or stay with my unit which, it was rumoured was to posted to Ceylon. Thus seeing it forty years later my romantic dream was not shattered, it is as delightful as I imagined it to be. Being the cultural and spiritual centre of Sri Lanka it was the stronghold of the last ruler of the Kingdom of Kandy, Sri Wickrama Rajasingha. It is the natural capital town for the hill country in the centre of the island. Situated seventy-two miles east, north east of Colombo and being at a height of some two thousand feet above sea level it enjoys a cool climate, a welcome contrast to the sticky heat of the coastal regions.

Attractive, pleasantly relaxing, Kandy is surrounded by hills and lush vegetation, amongst which are numerous hotels, rest houses and pensions. It is very much a Singhalese town. Full of attractions, good shopping, pleasant walks, the lake, and particularly the Temple of the Tooth in which is housed Sri Lanka’s most important Buddhist relic, the sacred tooth of Buddha. We visited the temple at a time when most of it was shut down for prayers. I was quietly expressing my regret to Robert when we were overheard by a passer by, who turned out to carry influence in the affairs of the temple. Enough for him to take us around several corridors and into the main room where many of the objects of interest were kept. It is sometimes difficult to know if one ought and how much one is expected to give in recompense. We seemed to have found the happy formula.

The Singhalese maintained the last outpost of independence in the Kandy hills until 1815 when the British spurred on by the commercial potential of the area overran the city without a shot being fired, deposed the King and finally accomplished what the Portuguese and the Dutch had failed to do in three hundred years. The rubber plantations were first introduced, followed by the vast tea estates. The spice and cinnamon gardens had of course been established long before.

As I turned over to switch off the light I began to wish I had planned for a longer stay. According to the guide book there is plenty to occupy one’s time, and being a natural bargain hunter and haggler I looked forward to our trip into town.

The following morning we went into Kandy and toured the main shops. We made a beeline for Gargills emporium. They sold most things we needed. Amongst the items I purchased were gauze, bandage, healing ointment to dress a sore on Jayanta’s shin. Ten days before he had burnt his shin on the hot silencer of his friend’s motorcycle. He had done nothing and said nothing about it until now when it was beginning to hurt.

Batiks where the next on my list. We searched the range of shops and boutiques along the main road out to the Peradeniya Gardens and eventually bought a selection. I had been looking for one batik in particular. In the entrance of the Casino where we had been the previous night I had noticed a very large and attractive batik. It depicted the Kandyan dancers who appeared in the show. I could not find anything like it and, enquiring of the owner of one of the main workshops he informed me it would have been a ‘one-off’ because, if as I described it to him it had included all the classical dancers and masked ‘devil’ dancers, no such batik would be manufactured for general sale. Designers would not mix the classic and devil-mask dancing. So I had to be satisfied with orthodox pieces.

Returning to Kandy town for lunch Robert suggested a visit to the government run Laksala, the arts and crafts centre. Many similar pieces, though perhaps of not such extremely good quality were on sale at almost half the prices I had paid. Robert bought a pretty scene of the Rama Sita epic for much less than I had paid outside the town.

Much to Robert’s dismay I suggested we lunch at the Empire Hotel. He pleaded with me it would be below standard. Which I expected it would be – that is why I wished to sample the rather rougher element of hotel.

I must say the food was wholesome enough but the method of serving it and the general seediness of the place caused me to drink more beers than I normally would have done, merely to help take my mind away from the pungent smell that permeated the dining room. When I wished to use the facilities I was directed upstairs. I had to pass by the occupants’ rooms. The rooms did not have doors, merely curtains. There was also a common room – used as a dining room by the half dozen ‘shoe-string’ young tourists I saw. The bathroom I was given to use was reasonably clean yet I would not like to have used it for bathing. I had done what I wished to do; at least now I knew what standards some tourists would accept.

It was with regret we had to leave Kandy after so short a stay, but on the next trip to the cultural triangle planned for later in the month we would be back again. We had so much more to see, the temples and the many sights around. We knew we must return.

On the morning of departure we had a very English breakfast of bacon and eggs. Jayantha and Ariyadasa, village, boys had by now mastered the use of the knife and fork, oftimes essential for eating European style meals. With full bellies and happy minds we set out on the A1 road to Colombo.