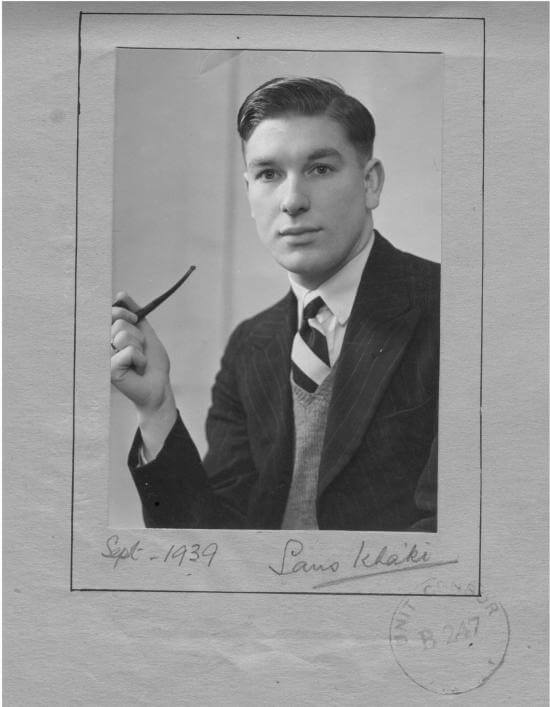

I joined the Army on the 17th of October 1939 as a Sapper (Private) R.E.

The Town Hall had always seemed to be out of bounds. It belonged to the Mayor, who I imagined sat in his parlour, resplendent in his robes and chain of office. The stone steps were the nearest I had ever been to the entrance and then only to be told by the municipal cleaner to “Op-it!” Along with several other young fellows we pushed through the doors and climbed the maroon carpeted stairs to the recruiting office.

The time had come for joining up, for me to have a medical, swear an oath and receive the “King’s shilling”. War had been declared two weeks before. When I told my Mother and father my decision a few days after Prime Minister Chamberlain had spoken on the radio declaring war on Germany they took my news calmly.

The first thing Father asked was, “What regiment are you joining?”

When I said I had not given it much thought he was alarmed at my immature approach. He asked me not to do anything until he had a chance to talk to someone. I did as I was bid and told only Owen Thomas, as he had to know because I had to give him notice.

The next day after lunch my father advised me to join either the Engineers or the Pay Corps.

“I’ve been talking to Harry Payling, (my old senior master) and he tells me you should join the Engineers. He says you will find a niche there to suit your talents, so tell the recruiting sergeant you wish to join the Engineering Services of the Royal Engineers.”

Which I did, and I was.

It was as difficult to say goodbye to the small staff at Thomas’s as it was to say goodbye to my family. Owen Thomas was non too pleased to see me go. He worried how they would carry on. I handed over to Laurence Brindley, the apprentice, then only seventeen years old. He would be able to cope with the day-to-day work for the cinemas and the occasional poster after which he would be in at the deep end. He did well, so well in fact, he left Thomas’s and went to work for Foremans of Nottingham at a huge salary until he joined the Fleet Air Arm.

The London Midland railway still operated from Mansfield in 1939 and I remember saying goodbye to my Father at the station. We were both so choked with emotion that the farewell was perfunctory – it was not until the train was well out of the station I felt the full force of my recent decision. I also found the Treasury note he had put into my hand. It was the first time I had owned a large white fiver.

The journey to Pembroke military barracks in Chatham by way of London was void of incident yet full of surprise. Although I had spent some time in Devon I had never been to London or the South East.

Chatham was a shock. I expected change and I got it. I found myself in one of six large hutments on the edge of a huge square, overshadowed by an imposing military barrack block and the School of Military Engineering. We were six squads each of about fifty men. The huts accommodated twenty-four beds in one section. The middle of the hut held the ablutions and the toilets and the second part of the hut had a further twenty-four beds. There were also two tiny rooms at that end, for the sergeant and for the orderly corporal. Our squad sergeant was an old hand. At first he appeared cold and harsh but we soon found he was a softy at heart. The more intelligent of us realised he could not afford to be, so we played up to him and smartened up. Those unwilling to learn were plucked out and placed in another squad.

Square bashing took a turn for the better when eventually we were kitted out with full uniform. After a week or two we were given world war one rifles and bayonets. They seemed unwieldy and incongruous when marching about in civilian suits and stamping on tar-macadam in shoes more suitable for dancing. My first pair of ‘ammunition’ boots weighed a ton, but they were a godsend when the snow and ice descended upon us.

Up at six in the morning, one had to be quick off the mark when forty-eight men share eight washbasins. Breakfast at seven, taking one’s own plate, knife fork and spoon. Back to the hut to “kit-up” and on station at seven fifty five for eight o’clock parade. The orderly corporal who took the roll call amused us with his aspirated cockney. He was a runt of a fellow, cocky, shrill and sometimes unconsciously funny, yet likeable. We were kitted out firstly with greatcoats for which we were thankful, for it was damned cold. At least they covered the motley collection of suits. After two weeks we were a squad of not unruly but not yet fully drilled soldiers. That took ten weeks more until we had been through the full training course.

I suppose I was lucky doing only two guard duties during my time there. The first was quite early when I had been there only a few days. To challenge someone on a cold dark night at the half closed gates of Chatham barracks armed with a pickaxe handle and to realise he was a major with a crown on his shoulder as he strutted past was to stammer: “Pass Sir! Sorry Sir!” To which he replied, testily: “Don’t we have a PASSWORD?” “Oh yes Sir”, which password I then told HIM. “Good God.” he groaned, “God help us!” With which he moved on without more ado.

Two days later the sergeant instructed us how to behave on guard duty. The next time I was on guard duty I stopped everyone and upset some of my pals who said,” Bugger Off, you know US!” I was on a charge twice, once with three others for walking across a corner of the square instead of round the edge. For that crime we had to scrub the floor of the sergeants’ mess. At the time we thought it a bit of a bind but as the mess sergeant gave us a slap-up eleven’s of hot sausages and tea we scored better than the rest of the squad who were out in the cold square bashing. The second time I was caught out was when a pal and I walked to Gillingham. By then we were to be N. C. Os – Lance Corporals. One Sunday in February we were told there would be no parade. There was and we were absent from the roll call. Strange to say the Adjutant let us off with only a warning. Maybe this was because we were soon to go overseas again.

Speaking amongst ourselves we more or less knew which of us in the squad were going to be certain of joining Engineering Services. One day early in December we were rudely awakened when twenty of us were posted to Trafford Park Hall, Manchester to join No. 111 Workshop and Park Unit. We were given sets of single stripes and told to sew them on our uniforms during the journey. During the several weeks we were at Trafford Park Hall we attended three lectures and spent the rest of time in Manchester either in pubs, cafes or cinemas.

Christmas loomed on the horizon. We were handed “five day” passes and told to get off home and report back on time. Within two days of returning from leave we were posted down to Chatham, back to were we started, only this time to have ten weeks intensive training at the School of Military Engineering.

The second time round we were not in the huts on the square but in the old barrack block. No big deal. The huts were warmer; the ablutions newer; and at worst in the huts one could see to shave. The ablutions in the old Victorian block were always short of light bulbs and many were the time we shaved in the shadow of a distant electric light. We were worked hard this second time at Chatham. Studying at the S. M. E. I learnt much of value, except typing. I had been used to working in my own fashion on my father’s old Underwood standard typewriter. At the S. M. E we had to use “Oliver” typewriters of World War One vintage. They were ugly designed machines. The lower and upper case each had their own set of keys. It was agony to type. To those who had never used a standard machine, to be taught on an Oliver seemed easy. I never mastered it without much effort and cursing.

There were times when the routine was varied and we had periods of physical exercise for which we marched to the gymnasium on the hill. We learnt a useful dodge and were not found out the four or five times we used it. If we knew from the ‘roneoed’ timetable the orderly corporal left lying around that last period in the morning was to be spent at the gym three of us we manage to fall in to be at the end of the squad. As we marched off the squad had to negotiate the steep hill and dangerous bend to the gymnasium. The N. C. O. in charge, on the Adjutant’s strict order, would always move to the head of the squad as we approached the bend to ensure we were safe from traffic thundering down the very steep hill. Half way up the hill at the bottom of the bend was a road to the left leading to the Seaman’s Hostel. At the right time, knowing the N. C. O. could not see us, we would peel off and proceed smartly to the Seaman’s Hostel to a warm fire and char and wad.

We were once thwarted when the N. C. O. brought the squad to attention gave a command “About Turn!” and we three found ourselves in the front rank marching all way round the square before starting up the hill to the gym.

Life at Chatham was not unpleasant; one was thrown into a whole new way of life and philosophy. One had to learn new tricks and adapt. One survived. At last the time came at the end of February to learn I was posted along with some of the chaps with whom I had trained to join C. R. E. No. 2 Airfields, Advanced Air Striking Force.

We moved to Aldershot to embark for France. We sailed from Calais on the Ben McCrea, a paddle steamer, which we were told, had plied between Liverpool and Isle of Man. Never a good sailor I made the best of it. It was not a bad crossing but the paddleboat wallowed enough to set me thinking about the owl and the pussycat and the pea green boat.

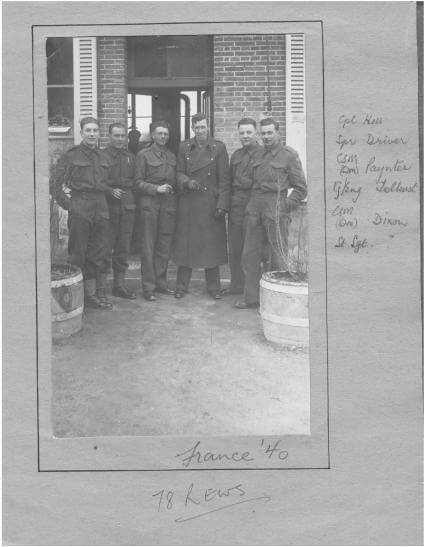

Our convoy of about eighty people ended up at Troyes. The Commander Royal Engineers, Lieutenant Colonel Heaton-Armstrong had a strength of about sixteen in his H. Q. The three Works Sections each about twenty-four strong were headed by Garrison Engineers. I was a lowly lance corporal and assigned to No 78 Works Section headed by Captain Tolhurst. In civilian life he had practised as an architect. We were never up to full strength the five years I spent in C. R. E. 2.

Life at the little chateau in Troyes was very cosy if cramped and after a few days No. 78 W. S. moved out to the small village of Anglure in the Aube. I spent two or three nights sleeping on a large hardwood bench-desk in a small silk stocking factory we had taken over. Then moving into the local cafe estaminet sharing a room with the staff sergeant. I moved from there rather quickly as I didn’t care for his habits and was lucky enough to find accommodation with a family of three in the High Street, the one street of the village.

Captain Tolhurst the G. E. was billeted with two old dears in the largest house in the village a few doors away. My main task was to organise the factory into a store.

A few days after we moved in three loads of grass seed arrived at the store. I was given a squad of Pioneer labourers in the charge of a ‘full’ corporal to move the machinery to one side and then stack the grass seed. The lads were good-hearted Geordies from Tyneside. However they looked upon the whole thing as a bit of a lark. In larking around they ripped and spilt bags of seed. Fed up, I asked the corporal into the quiet of the office. I put to him that they could do as they liked for all I cared, I didn’t give a fuck, but they would not be released until the Garrison Engineer returned. The Captain would decide on the mess they had made and their progress.

The corporal was a good chap and he flashed his pale blue Geordie eyes and said:

“Ooh ya bugger, y’wudna do thaaat wud theee. Don’t ye mind maaan, I’ll lick ’em into shaape.”

Which he did and thereafter I had no trouble. The bales were stacked so neatly the corporal earned praise from the Garrison Engineer.

Each Sunday morning I was pleased to be sent on the matchless motorcycle to Troyes to collect the mail. A glorious ride through the country side on an early spring morning, a lunch and chat with the fellows at H.Q. a quick drink in a local bar with a couple of pals and then back to Anglure with the mail. What a phoney war. Dunkirk happened in May. We knew nothing of it. There was a lot of strange activity to get the air strips operational and as suddenly we were packing up, saying sad fare-wells to our friends we had made in the village, we could give them no explanation or information of recent events – we had none. Nos 76, 77, 78 Works Sections pulled in to Troyes and formed up with H. Q. In tight convoy we moved west to Orleans where we stayed a few days.

I recall the dear old Adjutant, Captain Dennison asking me would I be so kind to accompany him to the Cafe de la Gare for dinner. I had spoken with him seldom but I agreed to go, at the time it seemed a strange invitation when he had brother officers to go with. We knew the French military custom and saluted the whole restaurant, mostly officers and a few ladies and made our way to a table under heavy scrutiny. The meal was excellent, it was so pleasant to have good service and enjoy the ambience. I remember so well the selection of cheeses offered on a four-tier dish. Heady on wine I remember too the dear old boy almost in tears as he explained why he had invited me. I reminded him somewhat of his own son who had recently been shot down over the channel. It was a sombre walk back to the billets.

Signs of panic showed as we travelled down the Loire valley to Tours and Angers. At one cross roads out of Blois we were held up by streams of citizens in cars, in carts, on foot pushing perambulators, pulling barrows and trucks. We were told that the Germans were pushing into Belgium and we were landing more troops on the French coast. Somewhat wide of the truth we were to learn later.