Someone pushed my shoulder. I woke up from a deep sleep. Blood was slowly seeping down my forehead. My passenger was slumped across his seat, his head resting in an unusual way near my shoulder. I gently pushed his arm away from me; no response. My God, he was dead! No he was not, he groaned slightly, then he groaned louder, he moved. Thank God. He was alive. I looked through what had been the windscreen. What a mess. It had been blown out and a pile of metal that had been the bonnet and right wing was piled up in front of my face. I staggered out of the car, the engine and the front of the car was all smashed up. About fifteen feet away was an American truck it too was smashed. There was no one around except several men standing by a Government lorry in the distance.

I went around to the passenger side and pulled the door open. H. Y. H. was obviously in pain. He complained about his leg. At this point several men who had been passing in the Government lorry came over and repeatedly said, “Praise be to God, they are alive; Praise be to God, they are alive.”

The student was now laid comfortably on the back of the lorry. Two of the men stayed with him. I climbed up into the cab. Then I realised something was wrong with my ribs. I was in pain each time I moved. We started to move off to the hospital when I cried out: “Stop!” I realised I still had something to do. I climbed down in great pain and went back to the car. I must not leave the vodka under the seat. There was only one thing to do, get rid of it. I ripped the top from the bottle and poured the contents away in the sand near the car.I asked them to help get him to the lorry. He couldn’t walk on his right leg. We carried him to the lorry as best we could; I felt weak and had a pain in my chest so they had to do most of the lifting. Good God what had happened? I looked around and took stock of the scene. It was like a nightmare. What had happened? There had been an accident. How? I could not remember. Where was the driver of the other vehicle, the truck that was all smashed up? There was no one in the truck. I kept on asking myself .How did it happen? I stood there, dazed, bewildered. I remember seeing the radiator grill lying in the sand twenty feet away from the car. It looked SO BEAUTIFUL and for one fleeting moment I thought it was all a dream. My car couldn’t have been so bashed up and ruined.

We drove slowly to a village hospital or clinic twenty miles from the town. During the journey I kept asking myself. How? What had happened? Try to remember. Think man think! I must have dozed off. Perhaps I had been given a shot. I next recalled being in an ambulance and wheeled into hospital. I must, have slept under sedation for next morning I woke up in a hospital bed in a room by myself with a policeman on guard by the door.

I rang the bell and asked the orderly where H. Y. H was. What had happened to him? He did not understand, or professed not to. So I had to wait until an Asian nursing sister came and explained he was in the same ward but I could not see him. How was he? I asked and was told he was O.K. but he had a badly broken knee. The peaked cap of the policeman on duty outside filled the window in the door. Why was he there? To keep me in? Or to keep others out? I needed to think how the accident had happened but I could not remember. I lay back and tried to recall how came to be in an accident in the middle of a desert with no vehicles around for miles except my Mercedes, a sheikh’s truck and a government lorry. How had all started?

I had collected the car the previous evening and the following day being a holiday had decided to go for a long run to put the Mercedes through it’s paces. I had not driven far when on the edge of town I met the student in the Karmen Ghia VW. When he learnt I was taking the car for a test run he parked his car and car with me.

I drove out on to the long winding road to the north of the peninsular. An oiled road made for the State by the oil company. It had recently been overhauled and some of old natural bends straightened. The car behaved well. I let H. Y. H. drive, for he was as good, perhaps even a better driver than me having driven huge American “Mack White” trucks when he was only eighteen.

We drove for miles, he chatting about the countryside and me yattering away about the benefits of training as I was want to do. We stopped for a drink.

I usually carried several cans of beer or lager when going into the desert. We each drank two cans of beer. Moslems are not allowed to drink alcohol. It was wrong of me to let him do so, but the heavy stuff is what they consider drink. Two beers on a sweltering hot afternoon had no affect whatsoever. However under my seat was a bottle of Vodka. I intended to visit friends later in the evening and this present would be very welcome in a society where drink was rationed on licence. Vodka. That was why the policeman was at the door. Emptying the bottle had been a bad mistake. Had I have left it alone sealed up under the seat my reason for having it in the car would be valid, now I had destroyed the reason and made myself look guilty.

Mid morning a European police lieutenant called to ask me questions about the accident. This sharpened my wits. I recounted how I came to be driving in the desert with one of my students. Times? How far did we drive? Who did the driving? Did we stop? Did we meet anyone? I answered all questions easily. Yes, I drove for about half and hour and then handed the wheel over to H. Y. H. We stopped after about fifty miles or so and enjoyed a cigarette and as the afternoon was passing I drove the car returning to town. Speed? I drove fast, how fast I couldn’t say. Perhaps fifty, sixty, or thereabouts. I asked him at what number the speedometer had jammed. He would not say. But he did say:

“You were not driving slowly, that’s for sure”.

But I could not account for the accident. I could only remember driving the car along the desert road, with the radio playing good jive music from the American air force station in Arabia. Then, nothing, I woke up sitting in the car with blood pouring from my head.

“I thought it was your ribs that had been broken,” said the policeman.

“Yes, so they I have, but I caught my head against the mirror or some flying glass from the windscreen gashed it. It’s nothing serious, just a lot of blood at the time.”

” Would you like a glass of water?” and without waiting for my reply he rang the orderly to bring a clean glass of water. We continued with the details of the accident. He was a decent chap. Younger than me, not at all officious. He told me I had been driving fast and from the traces of skid marks the Mercedes was estimated to be travelling at seventy miles an hour.

I asked him what happened to the driver of the truck. Was he injured, was he dead? He suggested I shouldn’t worry about him.

“He certainly isn’t dead in fact he has disappeared, he’s a Pakistani and they are looking for him and his mates. They probably thought they had killed you two. But that is not your worry. The Dodge truck belongs to a Sheik; he will find them but then again you have a lot of answering to do. Are you sure you can’t remember anything at all?”

I assured him I could not. I had nothing to hide but I remembered driving, tuning the radio, adjusting the sun visor because the road was facing due west. Perhaps I was driving fast, I was, after all testing it for performance. How I smacked into the Dodge truck, God only knows, I don’t.

Whilst we were talking a nursing sister brought in the glass of water. It reposed on a white napkin on a small tray. The police officer took the tray and offered it to me. I looked him straight in the eye, placed my right hand carefully round the glass, took a sip, and replaced it on the tray. As I have mentioned, he was a good fellow, and had the grace to give a little smile with slightly raised eyebrows. He went soon afterwards taking the tray and the glass with him.

My busted ribs mended after about three weeks. H. Y. H. spent several months on crutches after a successful operation on his kneecap. Mercedes boast their cars are made as safe as possible in accidents. This is true, had it not been for the booster to the radio that had been fitted under the dashboard. It had a metal cover the sharp corner of which cut into his kneecap.

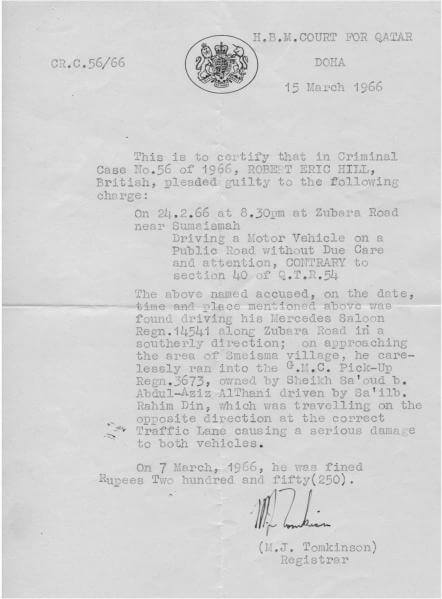

My case came up at the Crown Court convened at the British Agency about two months later. I took with me an Arabic speaking assistant from Personnel.

The assistant had warned me he had heard on the grapevine I maybe charged with dangerous driving. There was no point in me denying it. The truck I had, run into was smashed up and it belonged to an important sheikh. It could perhaps become political. I decided to plead guilty. The judge seemed a little disconcerted when I did so, but rallied and ranged through the penalties that could befall me for pleading guilty. I could be heavily fined and even sent to jail for a long period, something I had not thought about, I felt a slight misgiving hearing this. However, in a kinder voice he took into account my injuries, which he made sound greater than they now seemed, and he went on to fine me two hundred and fifty rupees. I got off lightly. The insurance company paid up for the price of the car. Although they did keep me off no claims bonuses for three years this was a small price to pay.We were early and shown into an anti-room and enjoyed a cup of coffee with the visiting judge. We trouped out into the panelled court together. The judge climbing to his chair on the dais, the assistant sitting in the well of the court whilst I climbed into the tiny dock, or was it the witness box?

The wreck was held in a corner of the Mercedes yard for some months when they approached me to sell it for scrap. As the insurance company had made an allowance for scrap value and deducted a minute sum from my claim it turned out the wreck was mine to sell. I did fairly well out of the deal. And, anyway I had already bought a replacement Mercedes before I left the hospital. Such was, and is, my faith in the strongly built Mercedes.

The second 230 Mercedes was a handsome car. It had standard type wheels and tyres that gave it a balanced elegance. The fatter larger tyres on the first Mercedes, much favoured by the Arabs for running on stony, bumpy desert did not look right. By the time the children came out for their holidays in the summer my broken ribs were healed and we had great fun travelling all over the peninsular in the Mercedes.

It had belonged to the Ruler and was a super car. It had extra fittings and dark tinted electric operated windows and there was no other car like it in the State. I had to own it, but the price would be far too high. Dare I start to bargain without losing face? I pitched it at a silly figure, so I thought. I offered five thousand rupees. Everybody smiled, for, as usual there were plenty of hangers on in the scruffy little office. I had blown it. Damn! Ah! Not so, Rashid started to bargain. We need ten, said he. No, said I, I really want it, but I can’t pay more than six, that’s all the cash I have, I said, lying through my teeth. As I have mentioned, they may have had a cash flow problem that day for after not too much humming and hawing they sealed the bargain. This left me a bit stunned. I had suddenly become the owner of this most splendid Thunderbird. I had also to part with six thousand rupees. This did not cause me any regret for it was a bargain, at the right time I could sell at a profit; meanwhile I had a marvellous car to enjoy. I appeared with it only once in the company compound. At that time I was Hon. Secretary of the Club and had parked near the entrance one afternoon whilst I went in to collect a file. As I had expected there were only a few members in the Club, otherwise I would not have gone in the car. I was I the office when a senior club member, knocked, came in and said he ought to tell me the Ruler’s car was outside the main door and perhaps the Ruler and his party were looking around. I thought he was taking the “mickey”. He thought I was being obtuse for I did not immediately respond. I asked him if it was carrying sheikh’s number plates but he didn’t know. Yell I do, replied. I was going to say, it’s not the old Sheikh’s car any longer, it is mine, but I welched and lamely said it belonged to some body in town and it was mine for the day. Why did I prevaricate? The car was paid for and had the legal papers. I suppose I did not wish to make anyone jealous.Soon after I had bought the Mercedes I met Rashid Hammam the younger of two brothers who were body servants to Sheikh Ali, the Ruler who had recently abdicated. They were classical Negroid Arabs; the elder was a large well-developed man with an ivory castle grin. His brother, Rashid, was a handsome man of great charm. The old, now retired Sheikh set them up with a garage to keep them busy and take the strain off his now reduced household purse. They had no idea how to conduct a business. They would hold their own court with their cronies and merchants who took every advantage of them. The cars they sold were usually second hand and came generally from the Sheikhs who wanted to keep in with the old Ruler. The Friday morning I called to see them they may have been short of cash for when I drooled over a beautiful low-slung Thunderbird they offered to sell it to me.

The Thunderbird was kept in town in my little Arab house near the airfield. With dark windows no one could recognise who was inside the car, so it was great fun to drive around town, except, of course the car was too conspicuous. Not only that, I had to drive to town in my Mercedes, take one from the garage, drive the other in undercover. Oh dear, no! It was all too much trouble. I sold it for six thousand, the sum it had cost me nine months previously. , One day, having taken the car to the Mercedes garage for servicing I walked around to the office of Ahmed Manaa. He had been building up the Peugeot agency for some time. I came away with the promise to buy a Peugeot 404. I was so sold on the car, the performance, the light and yet firm steering, the, cheeky response from the engine made it attractive. It was of course, very different to my Mercedes. I had an offer for the Mercedes from a chap in Abu Dhabi. Had it been anyone else in town I would not have let it go. Meanwhile, whilst this transaction was in the pipeline I took delivery of he 404. Fellows in the Club would twit me about starting up a hire car business, or was it a new second hand market I was going into? They had their fun, I was having mine at little cost, so far I had lost very little if any at all, on my car deals.

A Peugeot 404 is not in the same class as a German Mercedes. However, the French do make good cars. The main feature about the 404 was the very strong. The chassis cross member beam supporting the front of the engine. It gave the steering a very positive touch and made for an easy ride across very rough country. The extra long shock absorbers, or “jumpers” as the Arab mechanics used to call them, which were mounted on the front accounted for much of the smooth ride. I could drive over the very dodgy company roads at seventy to eighty miles and hour without taking too much out of the car. Of course, the tyres took a bashing. I managed about forty thousand kilometres out of a set before they needed replacing. Al though, I had a narrow escape just before I replaced them. I had driven across the peninsular one scorchingly hot day when, driving into town on the newly laid government road I heard a thumping sound. I imagined I had a very flat tyre. I was lucky I had been driving slowly; a large slice of the near front tyre was hanging loose. The wire ribbing had been cut through and the tube was almost exposed. Why it had not “blown” was a miracle. A pretty car, painted in metallic French grey it had neat upholstery which I supplemented with matching “cool” seats both front and rear. Why I can’t think, for I seldom, if ever, carried anyone in the back seats. I used the car for business and it earned its keep. It would move in deepish sand, although I had it bogged down more than once but that was usually when taking a secretary or schoolmarm on picnics and if, as we some times were, joined by a couple in another car, the resultant digging out added life to the party. It seldom gave trouble, it shouldn’t have, it was regularly serviced. In fact it was too cosseted. Every six weeks I took it in for an oil change. It ran on the purest oil of any car in the State. It deserved it for it was a good workhorse.

Towards the end of 1966 I had parted with the Mercedes. It went to Abu Dhabi and therefore I did not miss it. I liked it so much that I would not have been pleased to see it being driven around by someone else. You may well ask why did I sell it? “My answer would be, I don’t know. I think I was sorry when I sold it, but I had given my word and so let it go. I did not lose any money on it and I had had it for almost two years. I managed quite happily with the Peugeot. Being busy with my work, the car was not too conspicuous, allowing me to go around the peninsular without much notice being taken of me. Peugeot 404s had been introduced as taxis and, far from feeling –downmarket, I enjoyed the pleasure of being anonymous.

Whilst I still owned the Mercedes I often used to be overtaken by one of the Sheikhs of Wakra driving a swish Oldsmobile Starfire. It was a huge American soft-top. It had magnificent lines and I adored the car from afar.

I always gave way when I realised a son of the Sheikh of Wakra was behind me in the swanky red Oldsmobile. One day the car ran up behind me and stayed with me for some time. I slowed down to let him pass. As the car shot past the driver waved. I recognised him. He was not one of the Sheikh’s sons; he was the Sheikh’s Vizier, his henchman. He was inviting me to race. Which of course I did. This happened on several occasions and we kept up until we reached Wakra and he turned off to the Palace. Of course, I let him win even though he was only the henchman. I knew he carried quite a lot of weight with the Wakra Sheikh.

The day came when I was in the Peugeot and he passed by without recognising me. I gave chase and passed him. At first he was upset, then he saw it was the Inglisi he knew and not one of the taxi drivers, who, had it have been he would have intimidated by running him off the road. Some weeks later I again caught up with him in the Starfire. The top was down and he was driving sedately along, on his own, as usual. I waved, and swept past expecting him to take the bait. He drove on slowly, waving back at me almost in resignation. I pulled over on to the desert a little further along and waited for him to drive up. I had met him only twice before, but we knew each other’s status and were on speaking terms. In my best Arabic I asked him what was wrong. In his best English he told me the front suspension was in bad shape. I suspect it had been caused by him chasing over the desert and striking a large outcrop of rock. He said the car was “kaput”. He must have learned his few words of German when on holiday with the Sheikh in Frankfurt where they spent a lot of their time. I asked him if he wished to sell it. At first he appeared not to understand. Then I realised why. It was not his to sell. To give him a chance to “save face” I suggested he think about it and I would be happy to buy it at a very reasonable price. We arranged for him to contact me through H. Y. H. should he consider letting me have the car at a low price. I drove off back to Camp and thought no more about it. He must have mulled it over well and truly. He had one of the Sheikh’s cars with busted suspension. The Sheikh obviously had tired of it by letting him use it .The Sheikh would give him another car rather than spend money repairing an old one. Any money the Vizier received from me would be “baksheesh”.

H. Y. H came to see me a few days later and said the car was for sale. We saw the handsome young Vizier, and he agreed, after much bargaining, to let the Oldsmobile go for three thousand three hundred riyals, a steal. Before seeing the Vizier I had made enquiries of the Manager of Manai’ s, the agent for Oldsmobile cars; he was a close acquaintance of mine at that time, and I had a promise from him that the bill would not be much above a thousand riyals for all the work and spares needed to make the front suspension as new. It was with this knowledge I was able to bargain freely for the car. It was to r’ my surprise I had to pay so little for it. The cost of the repairs was one thousand four hundred riyals. So, for a total cost of four thousand seven hundred or around five hundred and twenty Sterling pounds at that time I became the owner of a splendid soft-top Starfire.

It was enormous. About eighteen feet long it was sculptured in ultra modern style; the body’ flowed’ on a low-slung chassis. The metal trim was kept to a modest minimum and carried out in matt chromium finish. Very tasteful for it’s time. Quality finish and quality refinements shone through the bodywork and the fittings. The huge eight-cylinder engine developed almost six litres. Although it was a soft-top it had the usual efficient air conditioning system that gobbled up a lot of power, the gadgets and radio cassette sound system drank heavily from the battery, which looked quite tiny beside so large an engine. The roof, made from heavy materials folded back into a well. The electric motors, which drove the excellent mechanism raising and lowering the roof, also took its toll on the battery. Altogether that wee battery did a magnificent job. The Thunderbird had been ‘all electric’ it’s seats used to swivel and rise in all directions and the windows opened and closed at the touch of a switch. The Oldsmobile did all these things plus open and close the roof, the lid to the boot and lock and unlock the bonnet. Hidden electric motors abounded the length and breadth of the car. Mirrors moved, aerials rose and withered, doors locked and unlocked all by courtesy of that tiny battery.

On the floor almost hidden under the brake pedal lurked a switch bull t into a shallow rubber’ mushroom”. This operated the radio. One could surprise the passengers by asking, “Shall we have some music?” and then, sweeping one’s fingers of the right hand about six inches away from the radio dial, press down one’s foot on the hidden switch and bring in the music. Grown-ups and children were taken in for sometime before my young son made me repeat the operation so many times he spotted the movement of my foot. It was a wonderful car to take on picnics. It was also more enjoyable in the winter months than in the torrid heat of the summer. Driving across the peninsular I had to wear a leather jerkin. Yes, it’s true, a heavy leather ex-army jerkin. Cool seats were a must in Arabia, either you sat on one or you sat in a pool of sweat. With the top down one could set the windows at any height but this would not stop a draught riding around one’s back. I experienced this the first time I went on a long journey with the top down and a breeze blowing. Alighting from the car I stiffened up like a pole and remained in pain for several hours. After that I kept the old leather jerkin in the boot to wear on breezy days when the top was down.

The Oldsmobile ‘Starfire’ was used for pleasure whilst the Peugeot ‘404’ was used for work. I had two good cars and had to complicate the situation by being soft hearted.

In the Club bar one evening I stood next to Freddie F. He had finished ten years of service and had taken a deferred pension. He was due to go on the plane the next day had not yet sold his ‘Mini’ .Be asked me if I knew of anyone who would buy it. I told him about the Arab who bought and sold second hand cars in town. Be told me he had been to see the very man but the deal he was offered was so poor he would rather give it away.

“Well, how much has it on the clock?” I asked.

“Nineteen thousand” he replied.

“Miles or kilometres?” said I.

“Kilos, of course, it’s only just over a year old.”

“That’s quite a lot, it’s about twelve thousand miles isn’t it? You’ve clocked up quite a lot for a year.”

“Well, I suppose it’s about eighteen months since I bought it” said Freddie; “you can soon knock eight thousand miles in, a year, even here.”

“Then it has about paid for itself.” I twitted him.

“Come off it, it wasn’t all charged up to company mileage I’ll have you know!”

“O.K. Freddie, old son”, smoothing him down. “Tell me, how much do you want for the Mini?”

“Three thousand riyals or two fifty sterling, I don’t mind which, so long as I can part with it before I get on that ‘plane” replied Freddie.

“No thanks” I said as he offered me another drink, “I’m off to have my supper, I’ll be back about nine thirty and I’ll by you a farewell drink, and if you haven’t sold the Mini by then, I’ll buy – riyals or sterling, whichever you wish.”

Over supper my mind raced away. Why? Well, it is a good little car, I mused, in good shape, as far as I know its history. It has this new ‘hydrostatic, suspension that is supposed to take the bumps out of the road. In a Mini? If you believe that you’ll believe anything. I thought to myself. What am I going to do with three cars? I expect the children will be coming out this summer and it will be useful for Richard to learn on. This seemed a good excuse and I believed it.

I dug out my chequebooks and went over to the Club. Freddie was still in the bar. Well he would be, wouldn’t he? “Sold it yet?” I was hoping he had not, for I was beginning to warm to the idea of driving a little Mini and I had the excuse for buying it for Richard to learn on. “No, it’s yours if you want it.” So we settled down to serious drinking whilst I wrote out a sterling cheque that he said he preferred.

The children didn’t come out that year and the car was very little used. I drove it on odd occasions when I took one of the cars in to town for servicing. I would ask one of the work force to drive the Mini whilst I drove one of the larger cars which I would leave for servicing and drive back in them Mini. Driving so small a car was a change from driving large cars to which I become accustomed. It would have been a useful little vehicle for a teenage schoolboy to learn to drive. However that was not to be. It did not get a lot of attention from me. For one thing it was tight to get into after the space of the Starfire or the ease of the Peugeot. There were times when I popped down to the Club in it, but usually I spent most time in the Peugeot and a great deal of the time across the peninsular in the oilfield.

I was pleased with the little car. It was very like having a new toy when a child. Freddie had looked after the car; it was clean all round; the engine ran well, it had been properly maintained. The few scratches on the paintwork were easily polished out by vigorous and well rewarded efforts of the houseboy. He was at first proud he worker for a master who owned three cars his stock went up with the other house servants but the fag of keeping them clean wore him down. He soon had to be reminded. He then complained the car did not go anywhere when he had cleaned it. It gathered more desert dust to be cleaned off again.

One evening I went to the club for a quiet drink. Propping up the bar was the Company dentist. A genial soul, as usual well fortified with whisky. He said:

“I would offer you a drink, can’t afford it, cost of livin’ going up all the time, s’all right for you.”

“How do mean, it’s all right for me George?”

“Well, you may be able to afford it, doesn’t mean you should spoil it for the rest of us.”

“George, old boy, what ARE you talking about?”

“S’like I said”, he went on “You’re bloody well letting things get out of hand. It’s going too far when you give your houseboy a car to ride around in.”

“Sorry, George, I don’t know what the hell you’re going on about”.

“Well I’ll tell you again” said he, “Your houseboy turns up at our house in a Mini.”

“Since when has this been happening?” I said, beginning to fear he was right.

“Oh, he’s often in it, he goes all round camp in it.”

“Does he indeed, but not when I’m on this side of the peninsular, I will soon put stop to that” I replied. “Anyway, how long has he been working for you?” Mohammed had been ‘moonlighting’ for the dentist’s family for some months. Nothing wrong with that so far as I was concerned. I spent much of my time in the oil field on the other side of the peninsular and he did not have too much to do keeping my suite of rooms tidy. But I was put out by his deceit.

Knowing my movements he drove around in the Mini whenever he had the chance in fact. He had more or less taught himself to drive it. I liked Mohammed. He had been with me for several years. I trusted him with the keys to my quarters. He never drank my booze. I could leave money and valuables around and never worry; he was as honest as could be. But mischievous, yes, that was possible. When I saw him the next morning I told him I wanted him to see him after lunch. An unusual request on a working day. When he turned up I asked him:

“Which car should we take?”

“Why sah’ b. where we go?” queried Mohammed.

“We go to the office. You will drive, you can become driver”.

“Me sah’b?” he stammered.

“Yes, you. Why not? You can drive, can’t you?

“Me, no good driver sah’ b, no good to drive you.” I had tormented him long enough. So I unlocked the Mini, beckoned him to the passenger seat, and dropped him at the roundabout without saying a word. I knew he got the message but to be sure he never drove it again when I went away on duty I locked the keys away.

Some months later when asked by the communications engineer if I would consider selling I agreed to do so, at the same price I bought it from Freddie. The price was an open secret. John objected, I said O.K. then I’ll keep it. The bargaining went on for some days. Each time we met he said:

“Changed your mind yet?”

To which I could only reply. “No, same price I paid if you want it, you can pay in rupees if you like, the exchange rate is down, let’s see now, that’ll knock about two hundred rupees off, how will that suit? And the deal was done.